Almost every morning, I wake up and read a blog by a noted American historian. I have learned to do so before my half-hour meditation, as I need to regain at least a modicum of tranquillity to face the day, and the America she describes is a convoluted and often seemingly hopeless one. I marvel at her ability to write coherently, informatively and movingly almost every day. And it makes me envious.

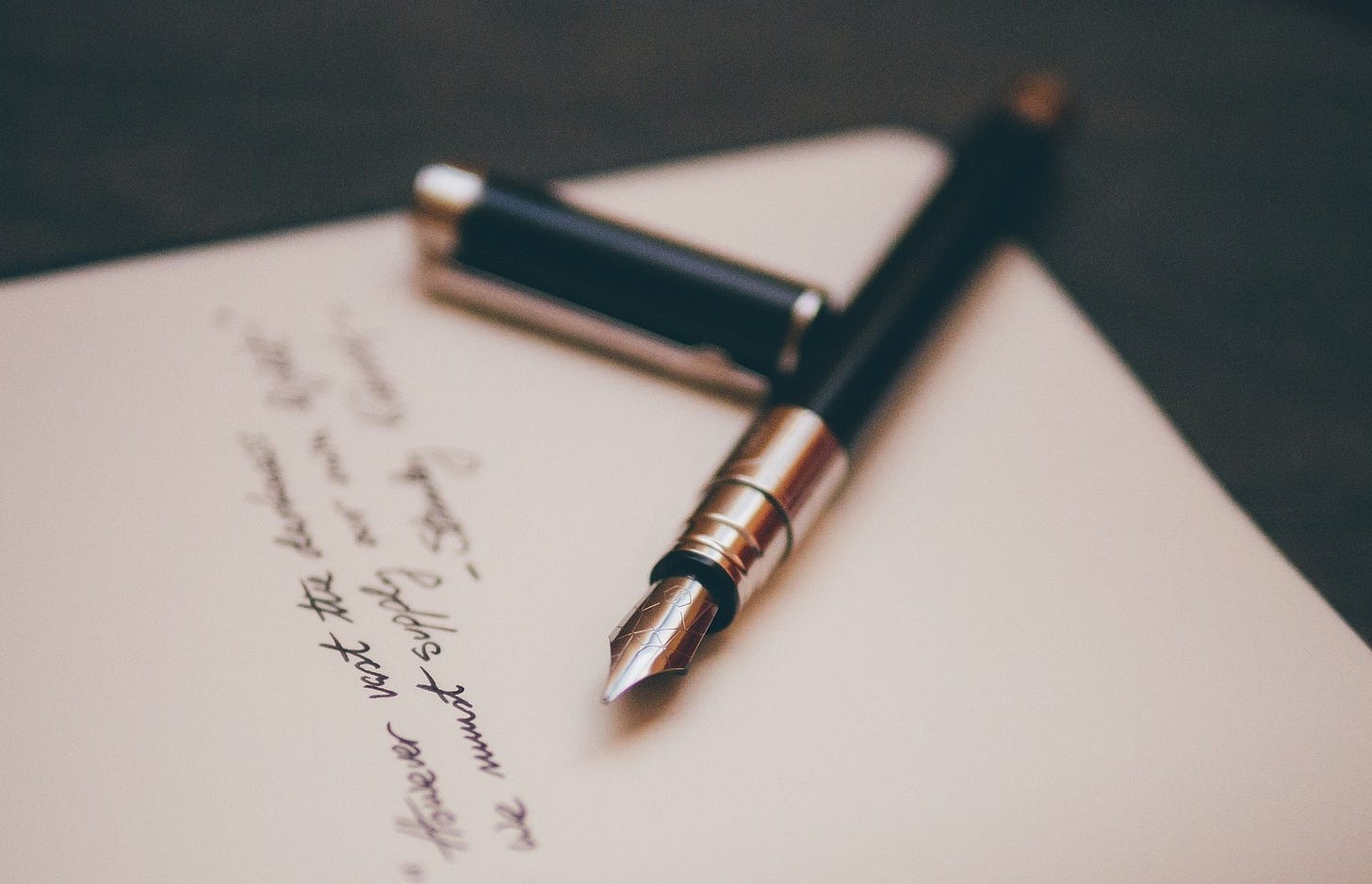

I used to write for a living, first, and only for a short time, as a young and idealistic journalist and later as an editor working in the public relations field. One would think that might mean I was comfortable enough to take my pen in hand to exorcise demons, write the next great novel (more likely, a torrid historical romance), or at a bare minimum, master writing the occasional story about some of life’s more profound or amusing moments. Not so. The mere act of putting words on paper, and yes, I still use a fountain pen, seems to me a solemn and truthful act, one of total commitment, something which cannot be taken back.

And that is why writing notes and letters to friends and family has become my most important form of communication — in thanking them, congratulating them, condoling with them or just cheering them on, I am able to find words that are not treacherous. Perhaps they will make the recipient feel better or express gratitude for a great weekend together, a delicious meal thoughtfully prepared, a life well lived, and for the culmination of hard work leading to personal fulfillment and success of all kinds.

These notes come from a deep place in me that sees humanity requiring love, support, encouragement and empathy. (And yes, like many of us, I write shorter, more formulaic messages to people less central to my life, who regardless of the depth of my affection require positive acknowledgment of something they have done).

What I have come to learn is that these no doubt old-fashioned, written-on-lovely-thick-paper-messages, which I send faithfully and as often as time permits, actually have become a stand-in for the words that might describe miles of personal pain, the words that could possibly form a slim novel, a short story, even a how-to manual or blog post of how to cope with things one thought only happened to other people. Words describing and recreating those wounds would, of a certainty, feel treacherous as they are seen through the veil of personal grief and the winnowing of my own history — not the five “W’s” every aspiring young journalist learns - who, what, where, when and why. (And not to forget the sole “H” – how)!

Objectivity, the holy grail of decent journalists, is not ground zero for Shakespeare, Tolstoy, Dickens, Rowling, McEwen, or Le Carré. Good and great writers do not worry about accuracy — they seek a different truth. They channel emotion, history, humour, whimsy, pathos, and in a magical, alchemical transmutation, create different worlds and extraordinary insights into the human condition. Their vulnerability is on display, and their pride is subservient to their need to create and understand themselves and the human condition. A daunting, terrifying task.

And so, dear Alice, permit me to tell you how much the writing of every author you have encouraged to contribute to A Considerable Age has touched me and how much I admire your collective discipline and devotion to your craft. Considerable talent seems to flow at a considerable age.

K.

A beautiful, thoughtful essay. I was moved, especially by the gracious sentence beginning "permit me..."

So beautifully written Kris! Over the years I am one of the lucky ones who has received and treasured handwritten notes from you. The care you take to find lovely paper and note cards combined with thoughtful words mean so much. C