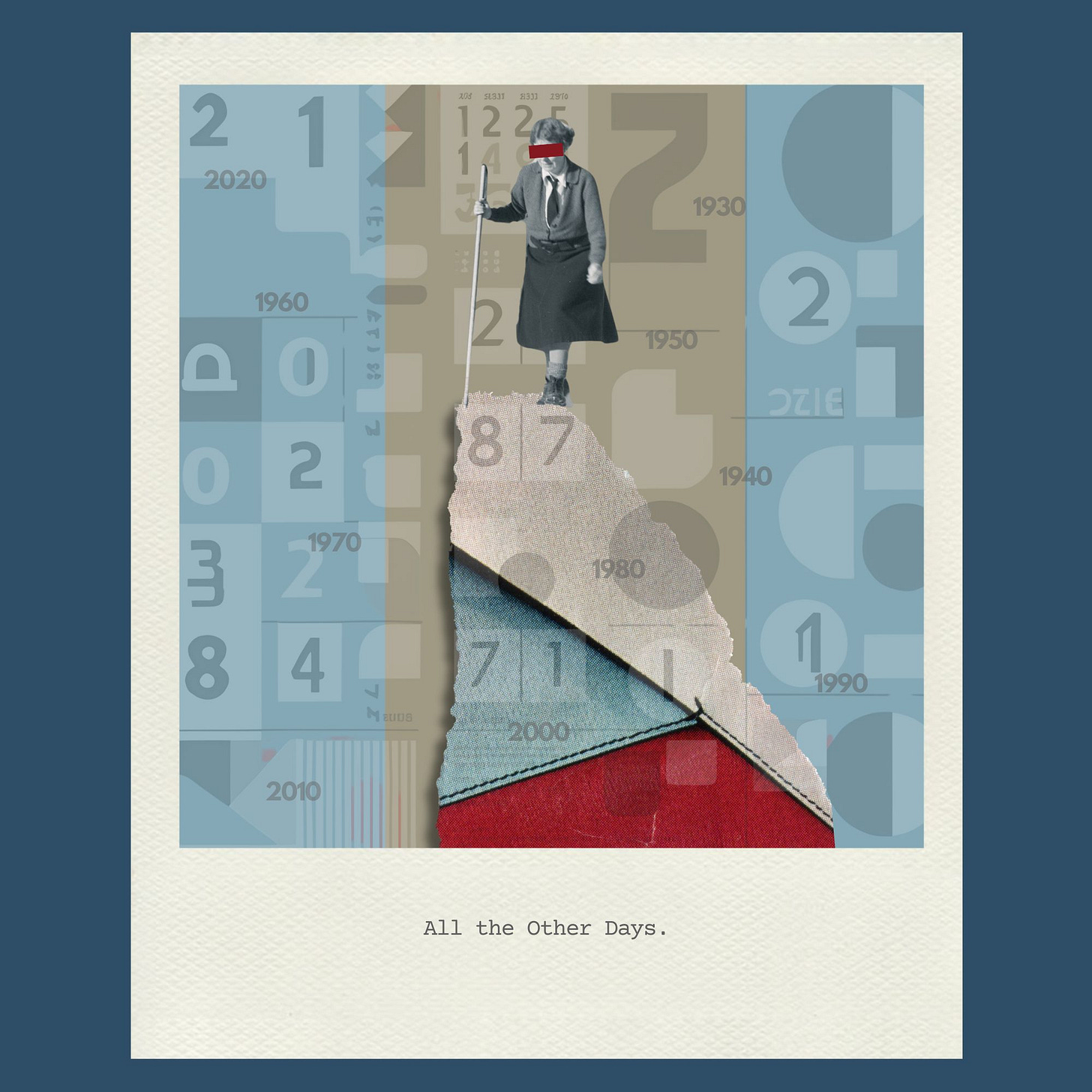

Pooh: One day, we will all die.

Piglet: Yes, but on all the other days, we will not.

I don’t know who decided it was fair game to put words A.A. Milne never wrote into the mouths of Pooh, Piglet and the gang. These memes almost always fail to capture the understated wisdom that Milne bestowed on his characters. But this one, Milne himself might have written.

A long time ago, for a few years in my late thirties, I owned a bakery franchise in a local mall. The country was in recession, and business was slack. I spent many hours idly watching people walk through the mall, not purchasing what I had to offer. Many of them were older women. Older, of course, is relative, and they may not have been so very old. But whatever their actual age, in my eyes, they were in their dotage, and I often found myself wondering how elderly people carried on with their ordinary lives without obsessing about death.

The inevitability of death began haunting me then, and it haunts me still. Even at my advanced age, it taunts me with reasons to deny it, then bashes me with reminders that I can’t.

“Coming to terms with mortality” is apparently one of those grown-up things we’re all supposed to accomplish by mid-life. I recall chatting in a parking lot with a couple I barely knew some years ago. How this topic arose, I have no idea. Perhaps I was trying to be humourous when I suggested to this virtual stranger that I was still denying my own mortality. In any case, the woman looked at me sternly and said, “You have some work to do, my dear.” She was no older than I was, but apparently had it all figured out. God knows, I have tried.

Mortality plays a prominent role in the theatre of my mind. I’m okay with it there—though sometimes I wish it would settle for just a bit part. But when it begs me for acceptance at that deeper level, where my sense of self resides, I put up a fight. And maybe I should. Many philosophers and scholars of evolution suggest that what separates us from the rest of the animal world is awareness of our own mortality, and denial of it is what keeps us sane.

I’m old enough to be grateful that I’m still around. Of course, I know I will die, and not so very far in the future. But I have trouble imagining a world without me in it, even as people I know and love exit the scene and, after a brief hiccup, the world hums along without them.

I watched my husband of fifty-four years die of cancer. I saw him gradually become a diminished version of his vibrant self, and I sat by him as his life ebbed away. A hiccup for the world, an earthquake for me. More than four years later, tremors of that seismic shift still rattle me. They jolt me into the reality of his non-existence when I am struck with a sudden urge to share news of a grandchild’s accomplishment; when a memory washes over me; or when I am possessed with a sudden need to know something only he could tell me. But the tremors have become less violent, less frequent, and the world does go on without him—as it will without me.

When I struggle to imagine my own non-existence, I experience the niggling and ridiculous delusion that I’m the one holding it all together for the people I love. That my very presence on this earth is some sort of insurance policy for my children and grandchildren, protecting them from impending doom. That to die would be to abdicate that responsibility. I know. Absurd. Where does such a notion come from?

Then, there’s the thought that I’d like to be around to see how things work out, as though life were a movie, and I don’t want to leave before the ending. Even now, when the world seems to be unravelling (I am clearly failing to hold it all together), I’m curious to see how it all unfolds.

On the other hand, sometimes I find myself thinking it would be good just get it all over with. The way you take a deep breath before ripping off the band-aid. Or steel yourself for a root canal. But wait. We’re not talking about a dental procedure here. We’re talking about that non-existence from which there is no return. So no thanks.

Cheery memes urge us to age with gratitude and enthusiasm, to face mortality with an attitude of carpe diem, to join the bucket list brigade. I envy those intrepid souls who rush into the unknown with to-do lists in one hand and a bucket overflowing with plans in the other. Alas, when I allow myself to focus on that shortening horizon, I’m more inclined to respond with a shrug and ask What’s the point, then? I suppose that makes me Eeyore.

So, with admiration for Piglet’s eternal optimism, and with due respect to Pooh and the woman in the parking lot, I think I’ll lean into denial for as long as possible—or for as many of those “other days” as I can.

Thank you, Paula, for your thought-provoking exposé. Last night, I was at a sugar bush in Quebec with my family for a fabulous meal of pea soup, eggs, pancakes, sausages, "oreilles de crisse" and maple syrup treats. This insulin-challenging feast was followed by singing, spoon tapping and dancing led by a chansonnier. Thoughts of dying were a km away. This morning, getting up with aches and pains, the End is reminding me how important it is for me to really enjoy those precious moments. I am praying, on this Easter morning, that I will be partying there again next year.

Excellent essay on The End which we all contemplate in our own way. I personally am always shocked at how comfortable I am about dying. But then again, it's not staring me in the face. Thanks for writing this. Janet