The gentle clink of porcelain, a silent bow, and the mesmerizing dance of autumn leaves in Kyoto—these are fleeting moments from a family trip to Japan in the 1970s. What I couldn't have known then was how these moments would echo through decades, unexpectedly intertwining with my son's journey through life, and my own brush with mortality.

One cold day in Kyoto, my husband Alan and I sought warmth in an ordinary department store for a cup of tea. We were not participating in a tea ceremony, merely having afternoon tea and taking a rest. I will never forget this experience and the man who served our tea.

Picture this with me. First, he placed a delicate white saucer quietly on my gold and brown place mat. He paused. He spoke not at all, but moved slowly with great intentionality. Surprised and affected, we felt an imperative to join him in the great silence. He then placed a teacup on my saucer, with the handle facing my right hand. He paused. After that he placed a teaspoon on the saucer and stood quietly for five or ten seconds. He then repeated this procedure for Alan.

This quiet gentleman left the table briefly and returned with his small, ebony tray. On the tray was a blue and white teapot, milk in a small white jug, and a small plate of delicate Japanese pastries. He paused and poured the tea into our cups. Then, looking directly at each of us, he asked, by virtue of a slight nod, whether we wanted milk. We did. His service was now done. He bowed slightly, paused, then left.

We were speechless. I was in tears, deeply moved by the man's presence and reverence. I did not know the word mindfulness at this time, nor would I have had the language to describe this as an experience of the sacredness of life.

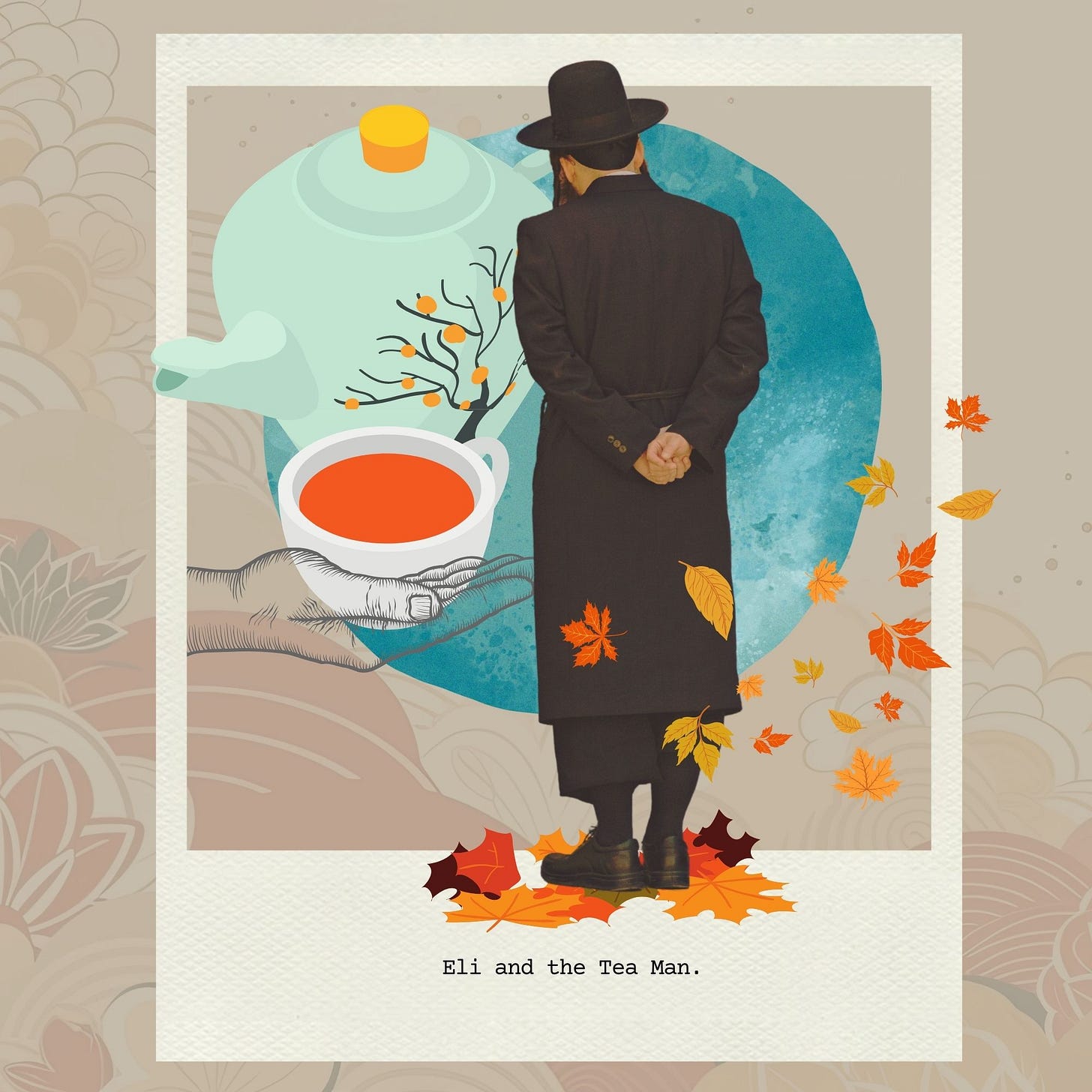

Years later, our oldest son Paul underwent a dramatic religious transformation at the age of sixteen. In what seemed like a very short period, he joined an orthodox Jewish sect known as Hasidism, and adopting his Hebrew name Eliyahu, became Eli.

Hasidic Jews are easily recognizable by their distinctive appearance: men typically wear black suits with wide-brimmed hats, and have long beards and sidelocks. Women dress modestly, often wearing long skirts, and arm and hair coverings. Observation of the teachings of the Torah are followed with great devotion. Equally importantly, the basic tenet of Hasidic Judaism is that the highest values are love, joy and humility—both in the service of God and in the treatment of fellow human beings. Little wonder that Eli, who had a sunny temperament, easy humour, and an innate generosity, was attracted to that branch of Judaism. Our son soon became devoutly observant and quickly became fluent in Yiddish, the language of his chosen community.

To us, this change seemed extreme and represented a complete shift from the lifestyle, beliefs, and culture of our secular Jewish home in which he had been raised. We were bewildered and saddened by his choice of a life choice so different from ours.

We consulted a psychiatrist who had written a book on cults. He asked many questions about Eli, and at the end of our hour together declared that he was quite sure that our son had had a genuine religious conversion.

We grieved, then, over a rather short time, were able to celebrate with Eli the deep happiness and fulfillment he found in his new life. Fairly soon Eli married a wonderful woman, Ilana, and over many years, they created a large family of fifteen children. His life enriched our own Judaism immensely, and because the family moved to Israel in 2006, we visited them and that challenging and fascinating country annually.

Although he had a deep inner stillness, more often than not Eli was in motion—galloping down the stairs, typing furiously at his computer, preparing hummus and Israeli couscous with sugar and hot peppers for Shabbat, or racing out the door late for evening prayers.

But one day, I saw Eli come to a complete stop and stand quite still for a moment or two. He then pulled a tiny square of microfiber cloth from his upper left breast pocket, opened it, and slowly and meticulously polished his glasses. When finished, he folded the cloth and replaced it in his pocket. He almost looked to be meditating. He stood still for about five to ten seconds and then went and stretched out on the couch, placing his feet on his daughter's lap. He began to beg shamelessly for a foot tickle.

The foot-tickle ritual I witnessed countless times. All fifteen of his children were called into service at some point or another. But Eli's exquisite, mindful cleaning of his glasses I only saw once. He was so vitally present on that day, that in witnessing our oldest son polish his glasses, I found myself summoned intensely into the moment, awake to the sacredness of all life. I was speechless.

Tragically, Eli died at fifty-two.

Less than four years after Eli's death, I was talking to Ilana. Customarily we had a long conversation on Friday mornings during which Ilana, who is a superb multi-tasker, prepared her famous feast for the family Shabbat dinner, always including her homemade challah. I shared with her the story of how Eli’s meticulous glasses cleaning reminded me of the tea service in a Kyoto department store so many years ago.

On this day, I was heading to the hospital for a CT scan to check if I was still cancer-free.

In response to my story, Ilana revealed that Eli had been transfixed by a video he had found of a man serving tea in Japan. She said he had watched it countless times.

"The apple doesn't fall far from the tree," she said.

"I will take Eli's spirit with me to the hospital as a blessing," I replied and choked up a little.

"Amen," she responded.

I am free of cancer.

Beautiful.

I can picture it perfectly!