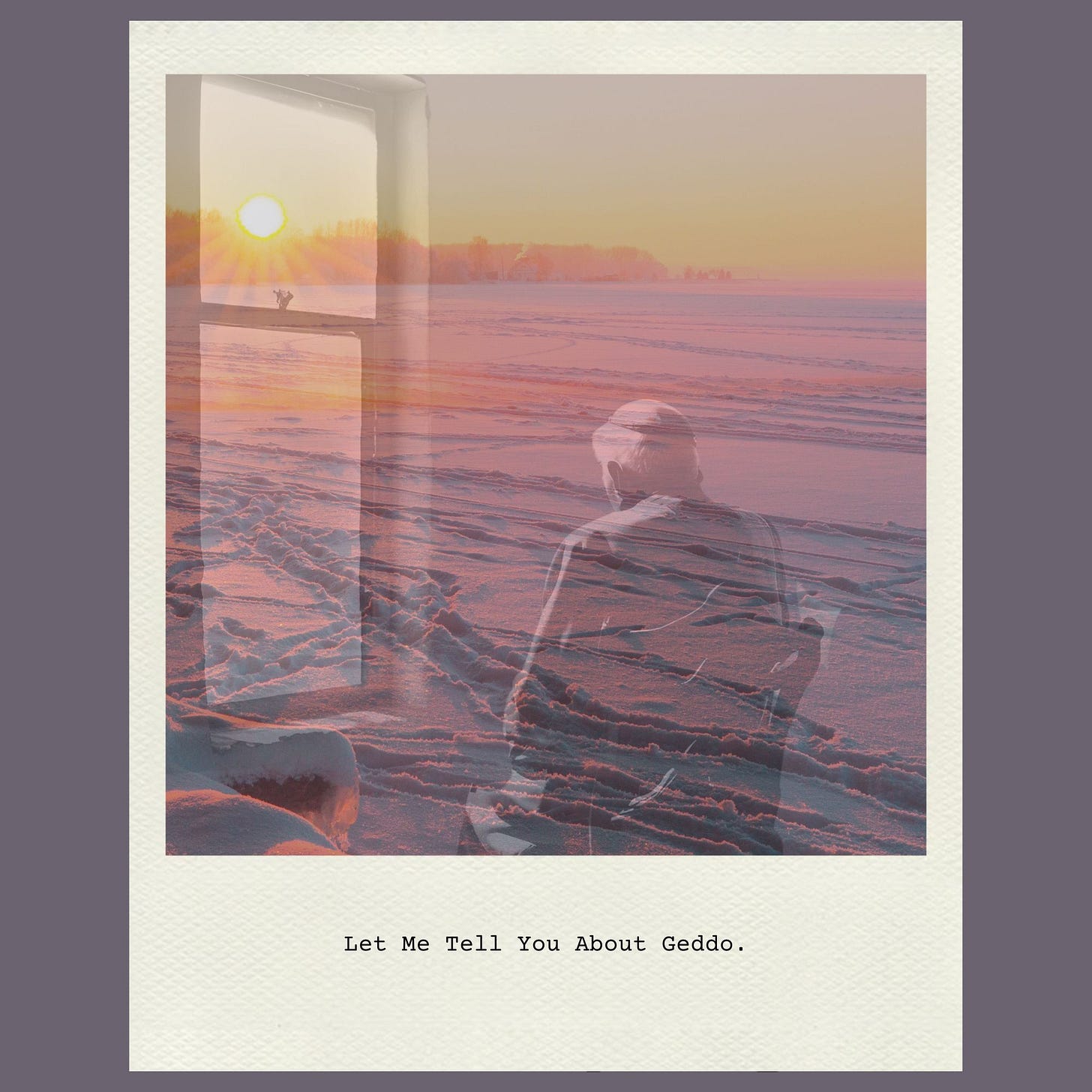

This week, as the days get longer and the sun melts whatever little snow remains in this weird and warm Ottawa winter, I’ve found myself thinking of my Geddo Ahmed, my mother’s father.

My memories of Geddo (grandpa in Egyptian Arabic) are scattered across geography, across the terrain of my life. Some of these memories live in Alexandria, on the huge, crumbling verandah of the old Grecian villa where he lived for many years and where we visited him each time we went to Egypt. Others live in the family room of my childhood home in Ottawa, in the patch of sun that slanted in through the sliding doors from the back deck when he came to live with us. Geddo would sit in that patch of sun all winter long, clinging to what little warmth this country would give him, staring at the blindingly white snow.

My grandfather, by the time I was old enough to remember anything about him, was forgetting. First his memories, then his habits, and finally, his way with words. Alzheimer’s was the first real disease I witnessed, and yet I couldn’t understand it. To a young child, Geddo just seemed grumpy. But as I got older, I realized. He’s upset because everything is so confusing, because everything keeps changing, because he used to know so much, and now it is just out of his grasp, no matter how he reaches.

My grandfather and mother had a special bond. They understood each other, understood their shared love of reading, and thinking, and debating. Geddo would wait for my mom when we visited. While my sisters and I played with our cousins she would sit with him for hours, sometimes outside on the verandah, and sometimes in his room, which I found so forbidding, with its books and old papers and ancient wicker cabinets. Everything placed just so, and trouble to come if anything was moved.

Immigrants say a momentous goodbye one time, and then spend the rest of their lives repeating it.

There were moments of levity, of course. In place of a massage, my grandfather would lie down on a haseera mat on the verandah and select a grandchild to walk on his back. We would clamour with excitement, ana ya Geddo! “Pick me! Pick me!” and glow with the pride of being chosen. The criteria for the job were essentially to be heavy enough and light enough at the same time—you had to be a Goldilocks of sorts.

There were rare moments when he was briefly lucid, too, and we’d have a lighthearted exchange, and I would remember what he was like when I was small, very small, before the Alzheimer’s. These moments were precious and fleeting, joyous and wounding all at once. You don’t even know what you’re missing, until it’s laid bare before you once again, and you feel your loss anew.

Aside from pictures, the only thing I have that belonged to him is my grandfather’s pumice stone. My mother gave it to me last year in a massive decluttering session, and it was only then I realized she had it. I think about the lack of ceremony. As she was leaving Egypt, maybe the first time, and maybe one of many times after, he wanted to give her something, or she wanted to take something, and somehow, it was this. The rock with which he rubbed away his callouses.

Immigrants say a momentous goodbye one time, and then spend the rest of their lives repeating it. They leave their family to go somewhere that isn’t familiar, that doesn’t hold their memories or their rituals or their ceremonies. Their families watch them leave, and maybe want to give them something. Something of meaning. Something to be remembered by. A token. But what can you fit in a suitcase among the logistics of leaving? What can you take when the bags will be weighed and there are limits?

One of my boys has my mother’s old wind up clock on his bookshelf. The other has her woven rug, the one that came with her from Egypt as she was starting her new life, a young bride, on the floor of his room. These are tokens that have meaning, that we’ve managed to preserve through the luxury of continuity. My parents have lived in Canada for over 50 years now. Things pile up. The boys have an embarrassment of riches to choose from.

But for my mom, so many years ago, she took her father’s pumice stone. And held onto it for decades. And needed to pass it down, not throw it away.

So fitting that something that cares for worn feet would be the totem your mother took to help ease her first steps in a new land.

What a beautiful, sad piece of writing. Thank you for sharing this