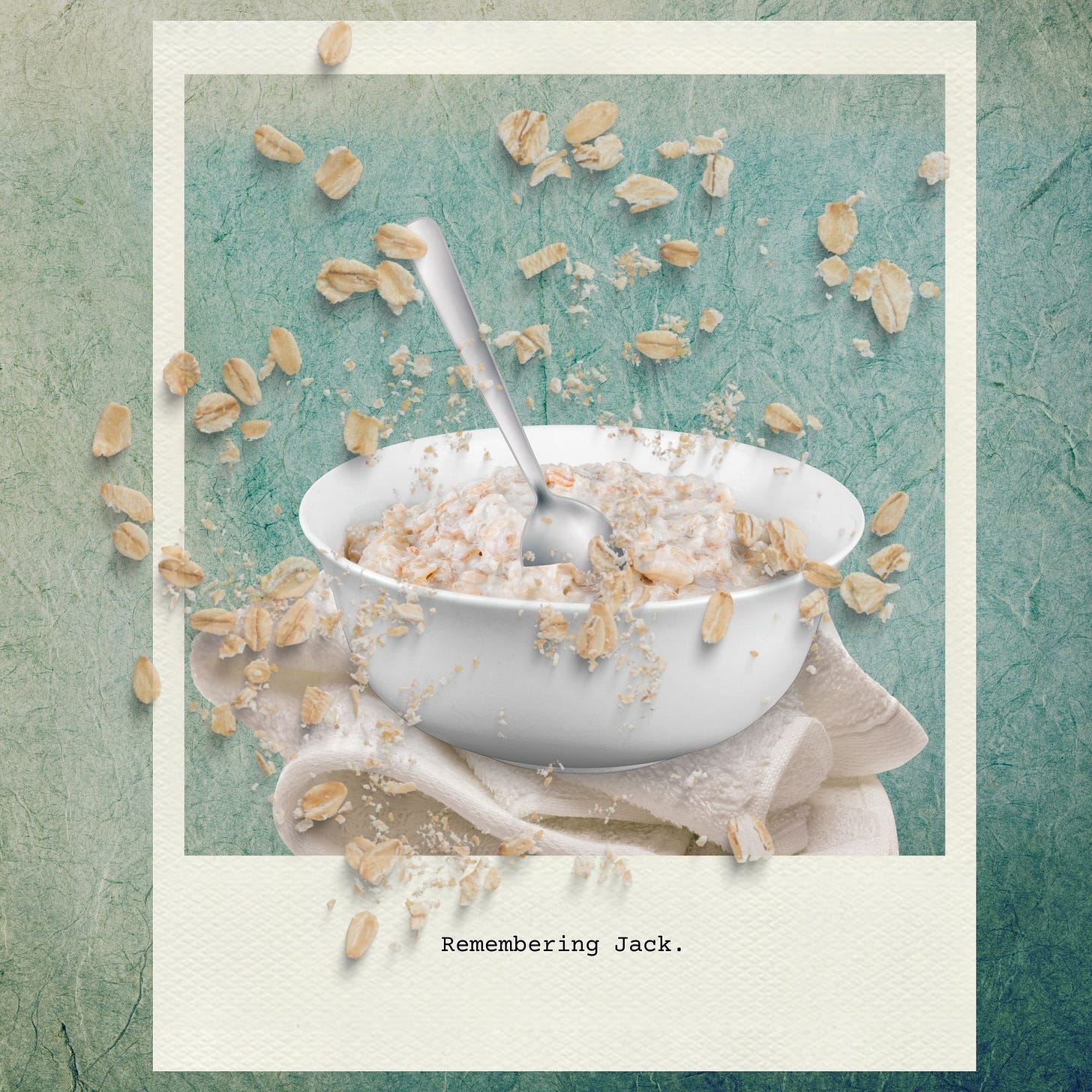

One of my tasks as the eldest in a family of seven children was to feed breakfast to my youngest siblings when they were babies. The job required me to stand by the big old pram—permanently parked in the narrow hallway outside our small kitchen—armed with a bowl of porridge, a spoon, and a damp face cloth to wipe spills from little chins. I resented the whole messy business—an affront to my big girl dignity. Pointless to complain to my mother. Maisie McCourt was a fierce little woman who did not tolerate mutiny. You did what you were told, no arguments.

I had been the first child to occupy that sturdy coach-built pram—ten years later, Jack would be the last. He was such a good-natured baby, with a shy, dimpled smile and plump, ruddy cheeks, that I never minded feeding him as I had the others. Approaching the pram, I would crouch down from the back and then suddenly stand up so that he could see me. He would pump his legs up and down in pure delight.

Jack grew up to be the tallest, handsomest, and funniest of Maisie’s five good-looking, quick-witted sons. He was also the first to die, outlived by all his older siblings. He was killed by alcoholism at the age of 52.

Jack had revelled in his place as the youngest in the family. He was petted and protected and adored. If he fell down, we would all rush to pick him up. As a teenager, he was a good soccer player and an enthusiastic drummer for a local band. Jack had many mates. The girls liked him, too. Occasionally, a girl would knock at our front door and shyly ask if “Jacky” was in, and could she please speak with him.

But he did poorly at St. Declan’s Secondary School, run by the Irish Christian Brothers. He struggled with reading and math. He was kicked out at 16, told he would amount to nothing. Intimidated by church authority, my parents were either unwilling or unable to stand up for him. In Ireland, in the 1970s, there were few learning needs assessment tools, no remedial programs. Kids like Jack were dismissed as being lazy, or worse, dumb.

At 18, he became a bartender at our local pub. He suited the job. He was warm and gregarious. The women customers were charmed by him, and the men liked his quick sense of humour. He could find the lighter side of any situation, no matter how dark.

I don’t know when Jack drank his first beer. I suspect it was in his early teens. Now, working in a bar, he was always around temptation. He spent the rest of his life in pubs—serving drinks, or, more often in later years when his health began to fail, straddling a bar stool alongside his fellow boozers, sharing his amusing stories, or opining incoherently on the state of the world.

Pubs were home to Jack. He once told me he felt safe inside their walls. It’s why he never married, he said. A number of lovely women had tried to “save” him, but he did not want to pass on to innocent children what he called the “curse of the drink.” He lived with our parents, financially supported, particularly by our mother, until he moved to his own apartment in his 40s after our father died. He kept a pet canary named Wharf.

I have had many years to contemplate why Jack drank to excess. What pain was he trying to escape? Was it his lack of education and limited job options? Was it in his genes, his DNA? More recently, I’ve wondered—without evidence—if he might have been abused at school. He was a good-looking, gentle boy, an easy mark for a predator. And the Christian Brothers were one of the religious orders found guilty of the emotional, physical, and sexual abuse of schoolboys in their care. Still, as I say, I can only speculate.

It might have been our drink-tolerant culture that ensnared him. Ireland’s celebrated writers loved to romanticize the booze, making it somehow noble and manly, not to mention a balm for the tortured artistic soul.

Nine years ago, my eldest brother found Jack dead on the living room floor of his bachelor apartment. The beer had ruined his heart and was beginning to destroy his brain. He had already had much of his life stolen from him long before he died two days before he was found. I was summoned to Dublin for the funeral. I boarded the plane in Toronto, shaken and weepy. My husband held my hand throughout the six-hour flight. We talked about the Jack we loved, recalling his soft voice and hazel eyes that could never fully conceal his deep sadness.

At the post-funeral reception, in the same pub where Jack had spent decades “knocking back pints,” the very wealthy owner took my hand and told me earnestly how “terribly heart sore” he was at my loss. Around the tables laden with free sandwiches and (not free) pints of Guinness for the men and rum and vodka coolers for the women, friends and family took turns eulogizing Jack. What a fine lad he was. What a great storyteller. Such a dapper dresser. And the jokes. No one could tell them better. And wasn’t he in a better place now? You could almost envy him.

Unable to stand the bullshit, my husband and I slipped out and went to an afternoon movie in a local shopping mall. I have no memory of the title, or the plot, or who starred in it.

Paula so many of us have lived with a Jack. Over the years, they become their disorder in the minds of those around them. No longer Jack. No longer someone’s beloved cherubic baby brother or adored youngest child. Your brother died too early as is often the case with addiction related illness. Some Jacks get better though because someone is brave enough to share a story like yours and it becomes their survival guide. Thank you.

“He kept a pet canary named Wharf” this line, this line. Heartbreaking and tender and angry - oh Paula.