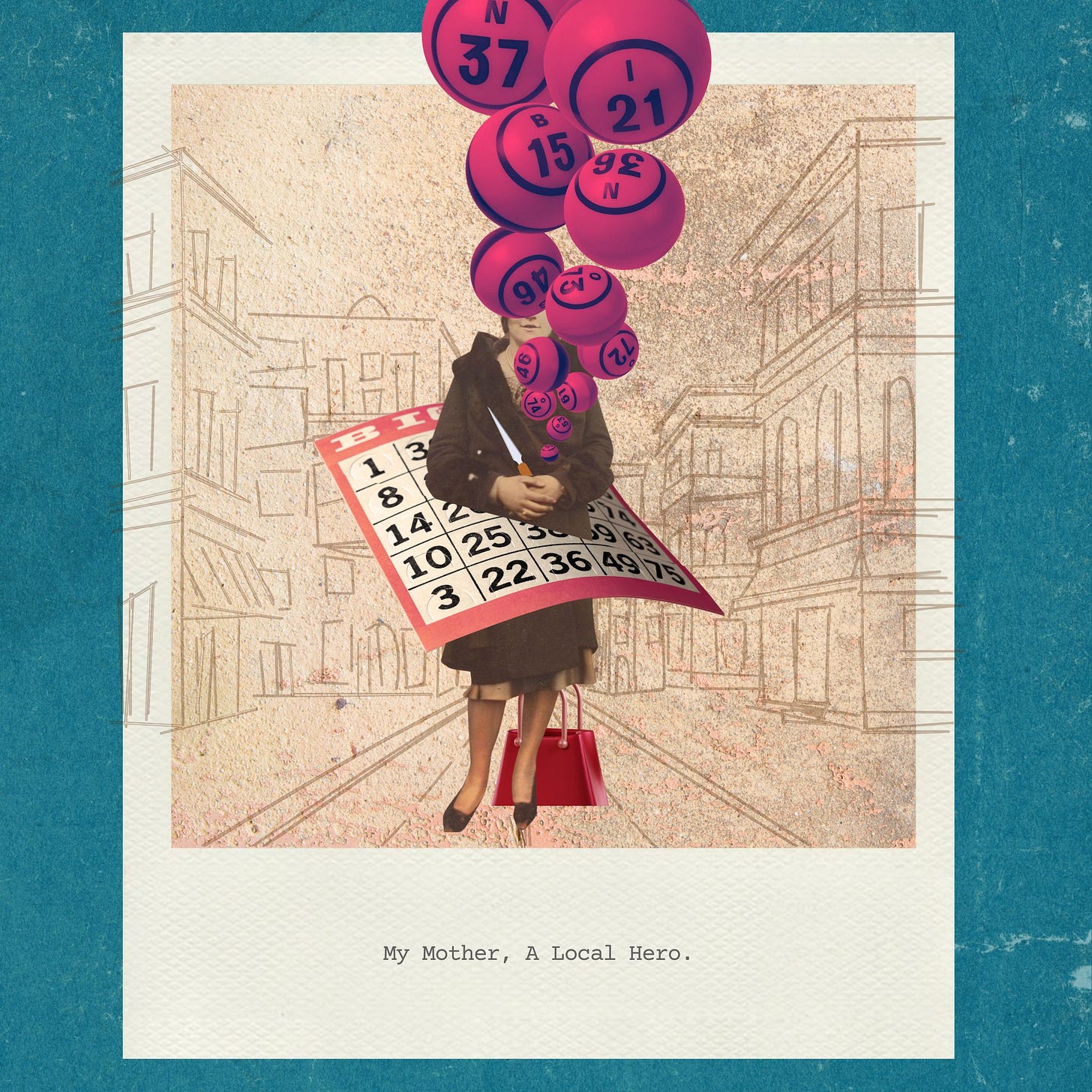

My mother, Maisie, once used a letter opener to ward off an attack by a mugger. This went down on a foggy November night in Dublin in the early 1960s.

According to Maisie’s account, she and her good friend Kate Ryan had just left Our Lady Help of Christians church, where they had enjoyed a game of bingo. As usual, the game was called with youthful enthusiasm by the curate Father Fennessy. Number eight, Heaven’s gate.

Later, as the women stepped into the mist caught in the yellow glow of the street lights, they were suddenly aware of someone coming up fast behind them. An arm reached around my mother, and a hand tried to grab her purse. She held on fiercely. The purse snapped open, and she suddenly remembered there was a silver letter opener at the bottom. With admirable presence of mind, she grabbed the “weapon” and, turning to face the mugger, she pointed it at his chest. In the failing light, it must have looked like a knife. She yelled something like, “Don’t you dare.” The man staggered away from her and fled into the night.

Before the thwarted purse snatching, the women would have been chatting away as they headed home, shoulders hunched against the damp air. The usual observations, speculations. Who was there? Who won the grand prize? Did you notice that Sally O’Brien’s got her colour back after the open-heart surgery.

They might even have asked themselves if bingo was truly gambling. According to the parish priest, gambling was a mortal sin—the worst kind. Every now and then, he would give it the fire and brimstone treatment from the pulpit at Sunday Mass. The hypocrisy of the church itself making money from the game and enabling addictive behaviour seemed to have eluded the good priest.

At that time, my mother might have felt guilty about the modest sums she wagered at bingo. This was before her Catholic faith began to slip away. And she would not have wanted the neighbours to be talking about her. She hated gossip. Found it ugly and upsetting. She used to describe our community of row houses and postage stamp yards as the “valley of the squinting windows.” This was the title of a book she’s read about a village where people derived pleasure from skulking behind net curtains to spy on their neighbours. The book was publicly burned by some villagers who believed—correctly—that it was about them.

Maisie was at bingo that fateful night, both to keep Kate company and to “get out of the house.” We, her family, were always telling her she needed to get out of the house. She might have preferred a more strategic game—poker or bridge. But so what? A friend is a friend, she’d have said. I’ve long admired her loyalty to Kate, who lived next door. The women supported and consoled each other through the difficult mothering years.

My mother didn’t have many friends. She liked people well enough. But she was awkward at small talk. She preferred her own company. She may have suffered from an undiagnosed agoraphobia. She was happiest at home with her books and her garden. Kate, a decade younger, was a bit frail and high-strung. Liable to have an “attack of the nerves” at any moment. She relied on my mother for advice on caring for her brood of five. Maisie—herself a mother of seven and a veteran of home births—even assisted the midwife when Kate’s two youngest were born in Kate’s bedroom.

“I can’t go through it without you, Maisie,” I can imagine Kate wailing, between contractions.

I remember as a small girl watching my mother in our back yard as she stood on an upturned pail and chatted with Kate over the brick wall that separated our houses. I imagine Kate, who was also short, doing the same on her side. They would be wearing scarves to cover the rollers they used to curl their hair in the fashion of the day—and always red lipstick. One or other of them—sometimes both of them at the same time—would have on a maternity smock they hoped would hide their pregnant bellies. It had the opposite effect. The talk would be of children, of cake recipes, of growing roses. It would have been punctuated by bursts of laughter.

The famous letter opener was inscribed “San Sebastian,” a resort town on the Bay of Biscay in Spain’s Basque Country. It was a souvenir from a trip that Maisie and Kate had taken that summer. My mother had popped it into a purse and had forgotten it was there until it showed up at precisely the right moment.

The side trip to Spain was my mother’s reward for having withstood the privations of an earlier three-day pilgrimage to Lourdes in France. Lourdes was her gift to the devout Kate.

It was the first time either woman had been on a plane. They’d never even owned a passport. There was some minor consternation before the trip when Kate shouted over the garden wall that she feared she’d never been born. When Maisie had calmed her down, she learned that Kate could not find a birth certificate in the city records. No official proof that she had ever lived. A quick phone call to our local councillor somehow sorted that out,

The night of the “bingo attack” as it came to be known, Kate had come flying into our sitting room, wild with excitement. We turned from the fire to hear her tale: “Your Mam was so brave; you should have seen her. She was such a hero,” she said. The mugger was a big lad and “was probably after money for drugs,” she added, wanting to heighten the drama. Embarrassed by the praise, our mother said, “Don’t exaggerate, Katie. It was nothing, really.”

When not many years later, Kate died of a heart attack at age 49, my father told me that Maisie took to her bed for days and barely spoke.

I think I’d have liked to know Maisie. A woman who knew the power of a good letter opener and who didn’t let brick walls get in the way of love and laughter. Thank you, Paula.

Another beautiful Maisie story!