Buried deep in my wallet are a photograph of my father taken in September 1955 at our family cottage and his business card, on the back of which he has written his name and address in blue ballpoint ink.

This photograph is folded in half, ragged, and worn. My dad stands on the boathouse dock at our family cottage in a white, long-sleeved shirt, having just arrived from the city and work. Peering into the water, our springer spaniel Sugar stands nearby, hoping to see a fish. The Peterborough wooden outboard is tied at the dock beside my dad, who regards the camera with a slight smile. I took that photo with my Brownie camera. I was 16 years old. He was 44.

I have carried it and the business card in my wallet for almost sixty years. Other photos and cards come and go, but these two items never leave. From time to time, I sort through the various papers, cards, and photos that inhabit the compartments of my wallet, always carefully returning the photo of my dad and his business card to their place.

I am totally unsuperstitious, I assure you, but I can also say with certainty that these two precious items will always stay in my wallet. My father died in 1965, two months after my first son was born. He was only 54, the age my youngest son is now. A civil engineer with a successful career and a dream to build a suspension bridge, he died of colon cancer. Colonoscopies were not a thing in those days. My brother and I, although in our twenties, never got over his death. Our lives were changed irrevocably. My children never knew him. To this day, I cannot speak of him without tears. And so, I cherish these talismanic objects.

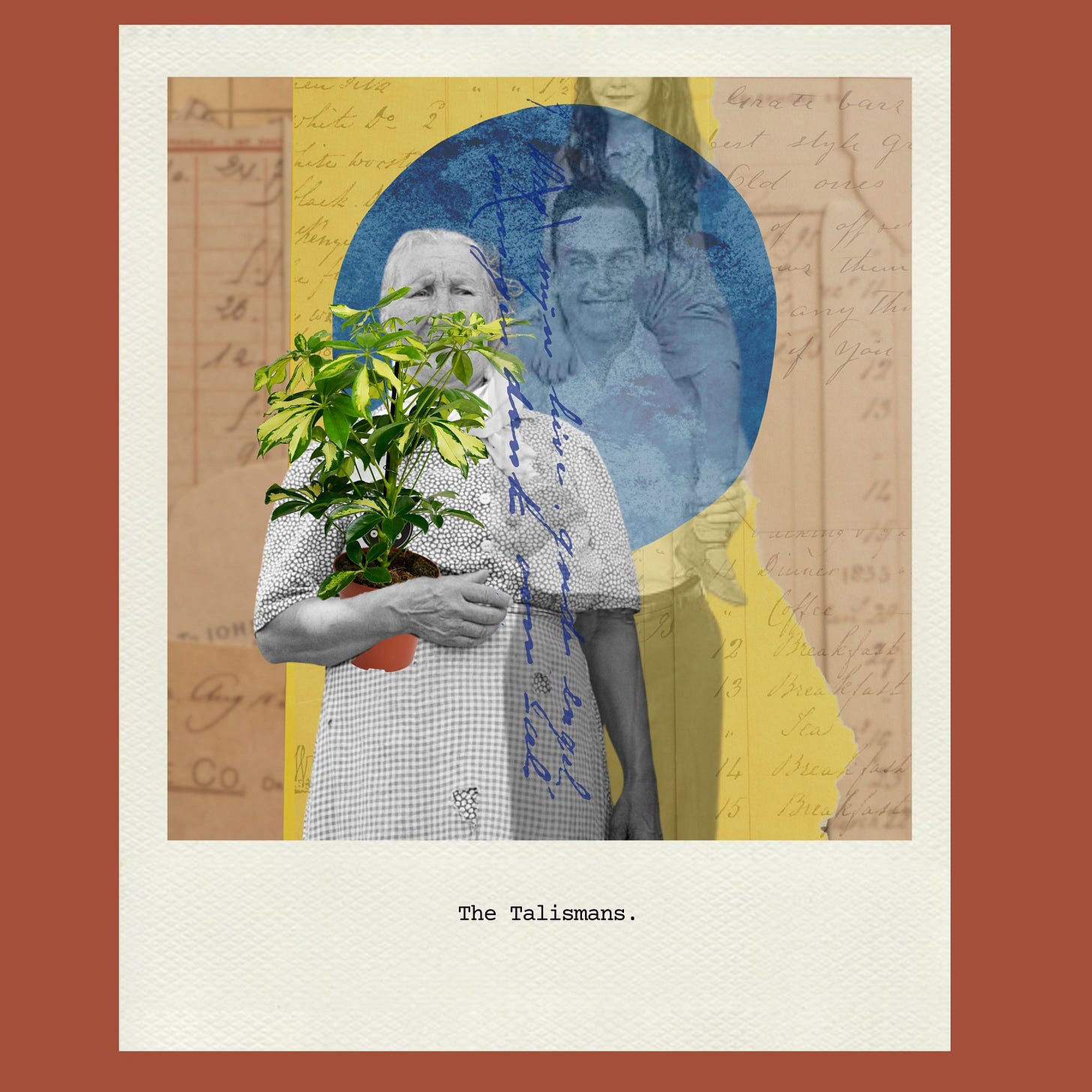

I call them my talismans today, but it is only lately, as I age, that I view them this way, as objects thought to have magic powers and to bring good luck.

And I now have another one, and it is a living thing.

In a small pot on the bathtub ledge, a Schefflera grows in my bathroom. I inherited that plant when my mother died in 1995. It is growing horizontally, some of its stems and green pointed leaves dipping into my bathtub and others reaching for the light at the window. It is completely pot-bound, but I dare not transplant this amazing thing for fear that whatever magic is keeping it alive will vanish.

From time to time, I polish its leaves. I fertilize it monthly from March to October. It rewards me with little shoots all year round. In the summer, when I go to the cottage for an extended stay, one of my sons helps me carry it out to the balcony off my living room, where it lives until we bring it in again in September.

My son carries the pot, I follow behind holding the stems and leaves in my hands. I have no green thumb, nor did my mother, but somehow this plant survived for her, and it survives for me. Like the business card and photo of my father, this Schefflera holds a special place in my heart, another talisman that I am convinced I need so that I will continue to live.

I am 85. My mother was 84 when she died of a heart attack on the way to a concert. She was a widow for thirty years. I can’t imagine what it must have been like to lose her life partner so young, but she lived those thirty years with vigour and enthusiasm nevertheless. I went to pick her up one day and as I drove toward her house, there she was, standing at the end of her driveway, her face turned toward the sun. “It’s good to be alive,” she said.

I have been a widow for six years. My husband lived to be 89. I am grateful I had him so long. Friends are becoming ill; some are losing their cognition, and some have died. Death and decline haunt me, as I know they haunt my dear friends. My children know, my friends know, and I know, that I will die one day. The question is how and when. I joke about it with my kids, saying things like, “When I die read all the memorabilia I’ve saved before you throw it away.” Or, “You can fight over (insert item here).”

I am not looking forward to that day. I cling to banisters, step carefully up and down curbs, sprinkle ground flax and walnuts on my breakfast yogurt. I will continue to live as best I can, in the (yes, irrational but comforting) belief that my father and mother are protecting me somehow from the beyond.

This is beautiful, Ruth. (I have the privilege of being one of Ruth's daughter-in-laws. She is my model for how to live life with curiosity, humour, engagement--and that daily sprinkle of ground flaxseed). xo

You make a poignant case for clinging to talismans. And speaking of clinging, please keep clinging to banisters, stepping carefully on curbs, and sprinkling walnuts on your breakfast yogurt - so we can continue enjoying your writing!