My mother and father slept in separate beds. Between them, a stack of detective novels and crossword puzzle books teetered on the night table. In the morning, my father would sit on the edge of his bed, fish around for his slippers and shuffle into the kitchen where my mother was boiling water for the instant Maxwell House, mixing the Minute Maid and tearing apart English muffins. Never cut an English muffin.

Once he settled in at the grey Formica table, he added the non-dairy creamer and the saccharine to his coffee and turned on the crackly transistor radio. He had gone all the way with Adlai back in '52, but most Americans liked Ike, and some even had a soft spot for Joe McCarthy. It was best to keep your head down, go to the shop, come home from the shop, eat your dinner and watch Father Knows Best, though he could hardly identify with the clean-shaven, suburban protagonist and certainly not with the sentiment conveyed by the title.

When I think about my father, the pendulum of my memories swings from affection to discomfort and back again. He was a decent man, but his animal nature, his essential wildness was somehow attenuated, left behind in a remote corner of a prehistoric past life.

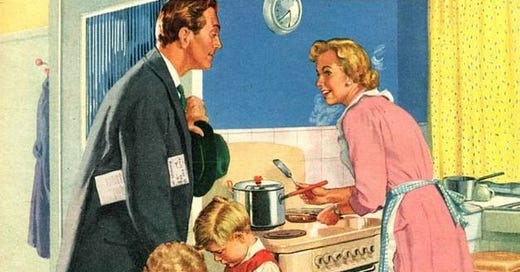

While he listened to the news, my mother would lay out his clothes—boxers, sleeveless undershirt, trousers, belt, shirt freshly pressed at the Chinese laundry, tie and tie clip, sports jacket, socks and cordovans. She bought and dispensed all of his clothes. He did not say, "I feel like wearing the green tie today." She managed his wardrobe like a pitching rotation, varying only in the event of injury, a spot of pot roast gravy on the scheduled tie. In the wall-to-wall mid-century malaise of the apartment on upper Broadway, there was no room for Daddy. Everything had its place. Dinner at 6.

My father didn't drive. A few times a year on a Sunday holiday, Uncle Jerry or Uncle Leo would chauffeur us in a two-tone Chevy and head north and west, crossing the George Washington Bridge into the untamed wilderness of Englewood or Nyack, where people had basketball hoops attached to the sides of their garages and barbecues for roasting marshmallows and kosher hot dogs.

In the kitchens, resplendent with breakfast nooks and the glossy patina of waxed linoleum, the women would arrange bowls of potato salad and dishes of pickles while in the backyards, the children swatted at mosquitoes and the men tended the fire.

You could see my father, eyes watering from some combination of smoke and wistfulness, staring into the blaze like a Paleolithic man the day he first discovered the sorcery of rubbing two sticks together. Pinochle games would come and go. Someone would have a second drink and tell a very bad old joke, salacious enough to induce smirking but obscure enough to leave the children bewildered. Someone else would make a thinly veiled racist remark. And still, my father would be staring at the fire.

His fixed gaze left you wondering what he was looking at in there. Some vision of the hunt, a large carnivorous animal tramping around in the brush while he, stands behind a leafy tree, waiting for just the right moment to hurl a rock that fells his prey and provides the family dinner. There he is with his hands clasped behind him, rocking back and forth on his heels, the blood in his veins mingling with the dimly remembered blood of a creature he would eat, the smell of the flesh rising to his nostrils with the grilling Hebrew National franks. He sees his haunches draped in the skins of some previously slaughtered beast. He is close to them, the animals, eating them, wearing them.

Always on the lookout, his vision and hearing sharp, penetrating the deep silence of the forest, not overwhelmed by the wailing of sirens on the Avenue, the constant burbling of the television.

After all, the survival of the family depends on his acuity, his speed and strength. He is his most authentic self singeing his eyebrows in front of the fire. But then, with regret, as the light begins to fade in some cousin's backyard, my father drags himself away from the embers and submits to Manhattan, a short man engulfed by tall buildings.

So good. So poignant.

“She managed his wardrobe like a pitching rotation.” Eloquent, evocaand sharply observed. How that time constricted women is an old story. We hear less about the impact on men like your father.