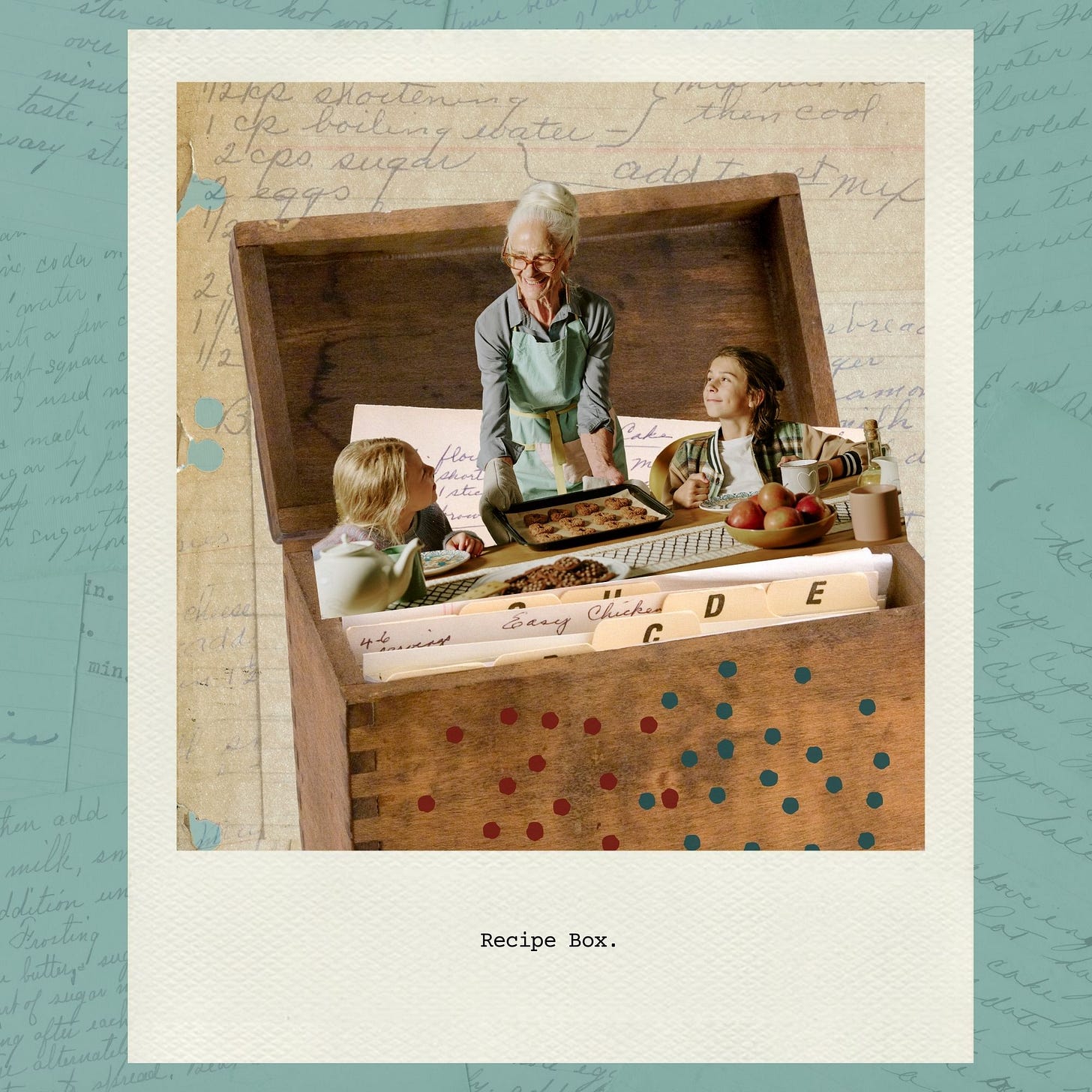

Recipe Box

“But what about the family recipes?” my mother cries. “What’ll happen to them if I have no kitchen?”

The recipe box, covered with butter smears and dusted with flour, is where she keeps her grandmother’s scone recipe. Years ago, when I came home from the hospital with my infant daughter, Mum was waiting for us with a batch of hot scones. Soon, perhaps, she will never bake again. A sad thought for us both.

But she’s in her eighties, with osteoporosis and serious heart problems. Though she still lives alone, in a suburban condo with a view of the Ottawa River, twice in the last weeks, Mum has made a panicked call to 911. She rejects the notion of a live-in or even a part-time caregiver. The companion who rushes from the adjoining building to accompany her to Emergency is her capable sister Do, who’s ninety. I live an hour’s flight away in Toronto and come whenever possible. My brother has a half hour drive to her place and is as attentive and helpful as a busy man can be. But now, we wonder if it’s time to contemplate a move.

And so I fly in and make an appointment, just for an exploratory visit, at a retirement home downtown where a friend’s mother lived happily for years. Mum, my brother, and I walk in with trepidation. We all love the sunny apartment where she lives now, and we remember the “home” where her parents ended up thirty years ago, with its sour smell of disinfectant, its lobby a parking lot of residents nodding off in their wheelchairs.

But in this lobby, we see vigorous seniors chatting with each other, smiling staff greeting residents by name, an elderly man playing a grand piano. “It’s good you came now,” says the manager who gives us a tour, “while you have a choice.” Most importantly, we learn a nurse is on duty twenty-four hours a day, and there are cords on the walls to summon help. Though we like the communal spaces, the first apartment he shows us is poky and drab. My heart sinks. But then he opens the door of the next. It’s a small but bright and elegant one-bedroom, with white carpet and big windows overlooking the river.

Then and there, we pay a deposit to hold the place for two months, while Mum makes up her mind. We return the next day to learn about the activities and outings, the library and the Scrabble club, and to have lunch in the restaurant-like dining room. Mum eats heartily while eavesdropping on animated conversations and laughing with the friendly waitress. My mother has lost thirty pounds in the last years. It’s great to watch her eat.

Back at her place later, however, what we’re facing dawns on us both. After my father’s death more than two decades ago, Mum eventually sold their four-bedroom house to move here. She endured the loss of many much-loved possessions to facilitate the change and still pays for a packed storage unit she never visits. Now we’re considering a move to two small rooms with no kitchen. Around us are cupboards overflowing with kitchenware, toppling stacks of books, newspapers, and magazines, closets stuffed with clothes and shoes, the walls covered with art. To list just some of her collections: eggcups, letters, tools, shoe shining equipment, knitting and sewing equipment, art books and painting gear, sheet music, pots and boxes, calendars, brooches, old English pottery, and old English silver, especially spoons. Many, many spoons.

This woman lived through the privations of World War II in England; she throws nothing away. How to clear out of here and squeeze into that tiny space? Would it be worth the effort and stress?

“Just the move might kill me,” she says gloomily.

“Yes, or it might give you a new lease on life,” I reply cheerily, pointing out the possibility of new friendships, life downtown with outings to the art gallery and theatre, to the market and shops. I remind her of one of my father’s favourite sayings: “To choose is to renounce.” If you choose this, I say, yes, you’ll renounce space, autonomy, and a lot of stuff. But you’ll gain something vital: safety. “You’ll be safe,” I say.

She won’t be safe; that’s a lie. We all know what’s coming down the pike, sooner for her than for most. But she’ll be safer. I will sleep better, knowing she has help nearby. Am I pushing for this difficult move only for my own peace of mind? Partly. But why, too, shouldn’t this vibrant woman live fully while she still can? Why not enjoy these years with no dishes to wash or food to shop for and cook, with new friends and concerts and especially a built-in nurse?

We face a mountain of hard decisions, downsizing, packing, and relocating if she says yes, and ongoing anxiety for all if she decides no. It’s up to her. But before too long, I hope to visit my mother in her new, sunny, very small living room. I hope to meet the friends she has made and hear about her excursions and her Scrabble score.

And I’ll bring fresh scones from the smeared, floury recipe box she has passed on to her granddaughter, my Anna, who loves to bake, and who one day will have to help me face hard decisions of my own.

Recipe Box is a chapter from Beth’s book Midlife Solo, an entertaining, witty, laugh-out-loud read packed with wisdom.

A lovely account of the crossroads many of us have faced with our aging parents - and some of us are beginning to think about ourselves. Thank you.

In ten years, I may be where the author’s mother is today. One thing that struck me while reading the story is the amount of « things » the children will have to dispose of in the mother’s move to a residence. I think it behooves on my husband and me to dispose of (get rid of) the many, many « things » we are fairly certain our children will not want to « inherit »: the beautiful glasses that take too much space in the kitchen and must be washed by hand, the demi-tasses no one uses anymore, the books no one else will want to read, etc. Not easy to do but easier for us to do now and, in the end, fairer for them as well.

Another point: I hope we can realize it’s time to move without our children needing to convince us that it would be better and safer for us to do so. Again, fairer for them.