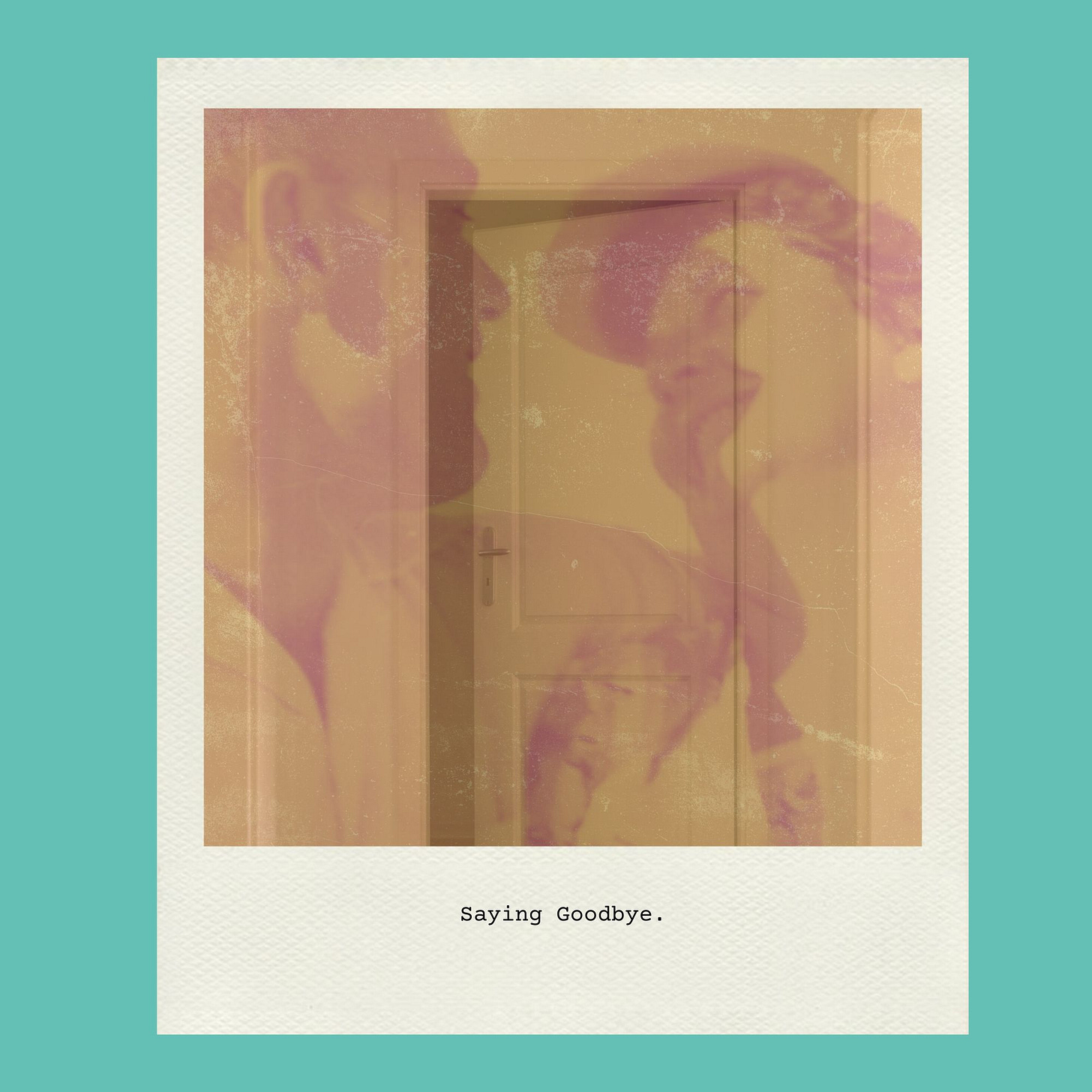

Saying Goodbye

There are eight faded robin’s egg blue dining chairs that remain, an Edwardian sewing table, a massive bookcase, a coffee table constructed of pieces of aged wood from India, another smaller bookcase, and a Victorian corner “whatnot.” I can’t use them. Peeking through the dark red paint colour on the walls of Dad’s den is the previous mustard shade, hidden behind the corner armoire that used to live there. The pale yellow in the living room below where the silver sconces used to be, is greyed and unsightly. I have kept those sconces, I think. They should be in a moving box. Somewhere.

In the end, it seems as if we are reduced to objects—those last goods and chattels that represented so much hard work, my mother’s excellent and light-hearted taste, and the austere disapproval on my father’s face as he got the bills. As reliably as Taylor Swift can fill a venue, Dad soon moved to accept the inevitable, as well as to a grudging appreciation of his comfortable, charming living circumstance.

I moved from Montreal to Toronto more than twelve years ago. My parents’ home became mine for my mostly twice-a-month visits, a combination of checking in and work.

Now, it is silent in the flat. No more deep Norwegian voice greeting me at the front door. No echoes left of the caregivers’ gentle melodic Tagalog. No kitchen bangs and rattles, no murmur of Bloomberg on the television, no soughing ghost of my mother, “no nothing,” as children say—just echoes of a chapter closed.

Where there was no grief before for either of my parents’ descent into dementia, just cope, cope, cope, I now feel a bitter bite in the area of my heart—no tears yet, though. So much anger at this disease that wastes fine brains and distorts, mutates and refashions those we love. So much childish resentment that they did not remain the pillars of strength they were always supposed to be.

Why did I never throw my arms around each of them and ask what they needed, what they wanted—I spent too much time instead telling them what they had to do as their cognitive abilities diminished. Perhaps we do become our parents’ parents as they lose their former touch points, but surely, I could have done it with greater grace and a dollop of humour—less an efficient administrator, more a tender daughter.

I am in love with many television series from South Korea for some reason—I have even mastered hello, goodbye, sorry and thank you. I’m working on please and excuse me—it’s a complicated language, and my own age is against me as my memory starts to diminish in the language retention department.

One of my favourite series is Navillera, a story about a young, exquisite, troubled ballet dancer and his eventual student, a seventy-year-old man who wants to learn ballet. Spoiler alert—the older man’s son, who does not get along with him, learns towards the end of the series that his father has Alzheimer’s. He breaks down, his disgruntlement and discontent with his father gone in a flash flood of expunged misery and hurt. Weeping, he embraces his father, telling him that he has always been the man he has looked up to and whose example he will embrace forever.

Such wisdom was not given to me as I muddled through 18 years of my parents’ joint metamorphosis. I forgot to find ways, other than saying, “I love you Mum,” and “I love you Dad,” to acknowledge my parents’ ongoing humanity, and instead trudged through my shopping list of tasks on their behalf.

Even now, as I survey the objects that were witness to their lives together, I am thinking of how to give them away. I worry about the photos to sort through, the financial papers to discard, and the flat to be left clean for the new owners. I bat away the feeling that in all that sorting and eliminating I might have thrown out love and respect.

Going through those last photos, I reflect, albeit briefly, on what a beautiful couple our parents were, on Dad’s brilliance, Mum’s joie de vivre, how much they gave to my brother and me and our families, the fun they had with their friends over the years before life got hard, and how lucky we are to have been the recipients of their endless love, encouragement and generosity.

I collect the remaining bits and pieces of my parents’ lives and fling them hurriedly into Tupperware boxes to bring back to Toronto. Heavy rain is predicted, and the hundreds of kilometres of Hwy 401 are bleak at the best of times.

And then I shut the door.

Eloquent. Sad. True.

Heartbreaking yet beautiful in its wisdom.