Kids can smell a phony—not to mention abject fear—from across a classroom, especially bright eighteen-year-olds who sit in the back row with that particular brand of teenage omniscience.

I learned this standing at the front of my first classroom, watching a cohort of exceptionally smart seniors size me up in seconds. This was 1982, at a massive, three-story Toronto high school that housed roughly 1500 students and boasted the most extensive gifted program offered in Ontario. Because they were so bright, they were also surprisingly merciful. They could have destroyed a rookie teacher, but instead they chose subtler forms of torture: the eye rolls, the theatrical slumping, the synchronized window-gazing accompanied by resigned sighs.

I got the job the Friday before Labour Day weekend, and spent the next three days frantically concocting lesson plans before showing up on Tuesday, heart pounding and hands shaking. I had just turned 24, which meant I was only five years older than some of my students.

I would be responsible for teaching several hundred of them over the next ten months, engaging a potentially hostile, probably bored, audience in an effort to see the seniors through to graduation. I was sure they would see right through me. Terrified, I was certain my first course of action must be to establish my authority and show ‘em who was in charge.

I ended my opening address to my gifted homeroom grade 13 class by sternly informing them, in my best teacher voice, strangled by a constricted throat and tripped up by a tongue desperately in need of saliva, "Don’t forget. I’m the boss.”

Even before the words landed, I regretted saying them. I watched suddenly alert students shift uncomfortably in their seats, and from the back of the room, I heard several tsk-tsks. Someone muttered, “So what does that make us? The workers?”

My mouth must have gaped open. I’m sure my cheeks blanched. I know my brain froze the minute I heard the retort. I probably just stared back blankly for a second or two, rendered speechless and embarrassed at having to backtrack and try to salvage the wreck of a day. So much for establishing my authority in the classroom.

A rookie mistake. In addition to being mortified, I practically bent over backwards scrambling to make up with them and present as professional for the rest of the period, pathetically pleading to be forgiven, especially by the girl who had asked the cheeky question, a perfectly lovely creature with a deceptively sweet face and a will of iron.

It took some time, but eventually we reached détente. It was a steep learning curve. I continued stepping in the muck from time to time over the coming months in my other classes, too, often with somewhat less than brilliant boys who, while never truly mean, seemed to get a kick out of messing around with me from time to time, metaphorically speaking, that is. Often as not, they were hockey, rugby or football players.

Further confounding the situation, I found myself so attracted to one of them, a handsome devil named Simon, also the football team captain, that I blushed furiously whenever we made eye contact. I’m pretty sure he had a little crush on me, too, but I was a newlywed for heaven’s sake! What was happening to me?

The solution I arrived at was to engage him in conversations, asking questions about his girlfriend—a gorgeous girl with a big 80s hairdo, whom I nicknamed Miss Texas, which pleased him enormously—and teasing him about being a ‘good’ boyfriend. Anything to keep that rosy flush from spreading across my face. His farewell comment to me at the end of the school year, written under his front row centre team picture in the yearbook, was charming. I was flattered to read he would miss me and relieved to hear him refer to us as friends, and happy to hear I would finally meet Miss Texas at graduation.

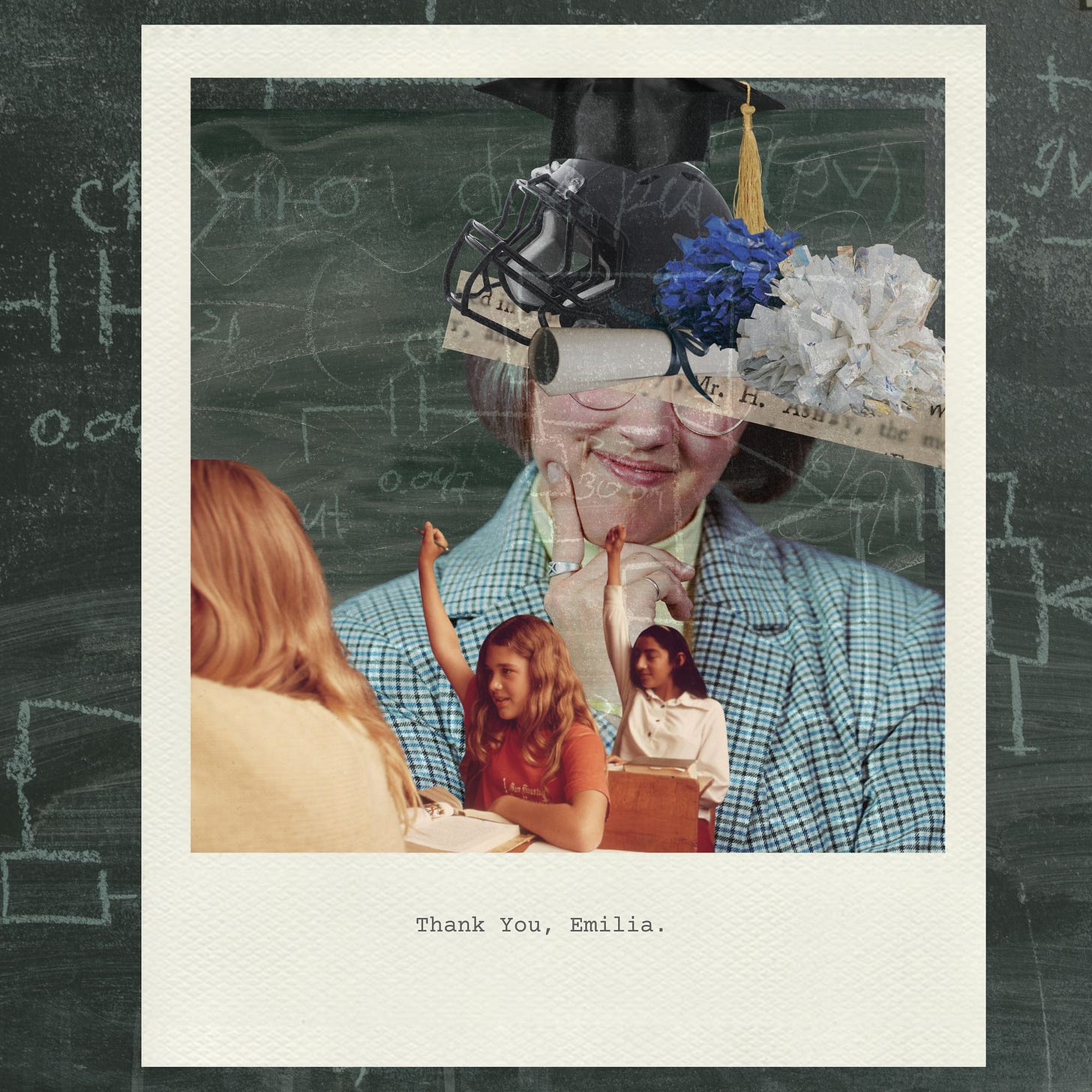

Having been a high school dropout, I never had a graduation. I really didn’t know what the whole five years were supposed to be all about at all, least of all what it would have been like to cross the stage in cap and gown to receive a diploma. What it would be like for normal kids, I mean. Kids who weren’t grieving the sudden loss of a parent, and worrying about the mental health of another, for instance. Kids who instead could focus on making the cheerleading team and running for student government and playing volleyball in the gym; kids who had long-term goals, who won scholarships.

When I became a teacher, no one was more surprised than I to realize how much I had missed those years. Nor how glad I was to have found my way back to school. I got to relive my adolescence in some wonderful ways: going to football games, being yearbook and student council advisor, even chaperoning proms gave me back something I had lost, and I loved every minute of it. No longer someone who didn’t, couldn’t fit in… I belonged. My mother used to say, almost accusatorily, “You love those kids.” She was right.

One of my superpowers was connecting with adolescents who hated school. Lost, sad, angry teenagers, the ones with eyes closed, or fists almost raised, the ones aimless and wandering alone. Having been one of them, I was very good at recognizing them shooting their mouths off at the back of the classroom, huddling in cafeteria corners or ducking into bathrooms, skipping class. Looking after the lost girls and boys who longed to be found by a grownup, by an adult who saw them—was the best part of my career. Other teachers used to wonder how I always knew what was wrong. I used to wonder how they could not have known. Just look—they’re a mess. Ask them what’s wrong. They spill their guts.

Luckily for me, that first class—Sue, Zinta, Briony, Arlene, Lisa, Bessie, Amanda, and especially Emilia—did not fall into that category. From them, I learned to understand and appreciate those cheerleaders and high achievers, those good girls I had envied so much, the ones I had wanted so desperately to be just like, but had been so dismissive of in high school. That class of kids provided a soft place to land for a new teacher with confidence issues and a sketchy secondary school background; they challenged and supported me, whether or not I wanted or needed either, and helped me cut my teeth as an educator.

Serendipitously, Emilia and I recently spoke for the first time in over fifty years. She told me how upset she was that I hadn’t been at her grad, especially upon learning the reason why—that I had lost the child I was expecting the last time I saw her, at the end of her school year. I was deeply touched by her response, the sorrow that remains with her to this day.

She brushed off my assertion that I was probably the world’s worst teacher. She countered by saying she remembered me as having been a pretty great one. We were both surprised at how much we remembered about our time together, and we plan to meet up one day soon for a real visit. Most astonishing to learn was that she, too, is now in her sixties.

In some ways, Emilia will always be that bright-eyed beautiful young woman who sat at the back of that classroom. My heart soared when she told me she had become a journalist—I knew it! I called it!

And so, after all these many years, I write to say this: the class of ’82 made me a better teacher. Thank you, Emilia, for the inspiration. I was grateful then. I am grateful now.

With your humility and sensitivity I imagine you as a model teacher who touched and influenced many lives over your career. Thank you for giving us a glimpse into your time caring about lost souls and bright minds.

Beautifully written Sarah - thankyou.