My daily phone calls began soon after my mum was diagnosed with cancer. When she got the terrible news, she was seventy-six, a grandmother of five, finally enjoying the fruits of the life she and my father had worked hard for. The doctor said they caught it at an early stage, and only surgery was required to remove the offending cells.

I called her daily out of a sense of duty and concern, but I felt guilty that I did not have more to offer. I had two toddlers, a busy job, and a life where something was going on every single moment of the day. She had my father, I rationalized, and they seemed to be managing. Looking back, it was my father who first called me with my mother’s cancer diagnosis. True to her character, she preferred to keep life’s burdens to herself.

When I phoned, sometimes my father answered, and we would exchange a cheerful word, maybe two, but he would quickly pass the receiver to my mother. She was the one who had cancer, I am certain he rationalized. But as I look back, in his way he liked to put her front and centre in her daughters’ lives.

"I am working on my stamps," he would say if I had the opportunity to keep him on the phone long enough to ask what he was doing.

After he handed my mother the phone, I knew he probably returned to his comfortable chair in the den to contemplate what to do next with the stamps he had laid out on the coffee table.

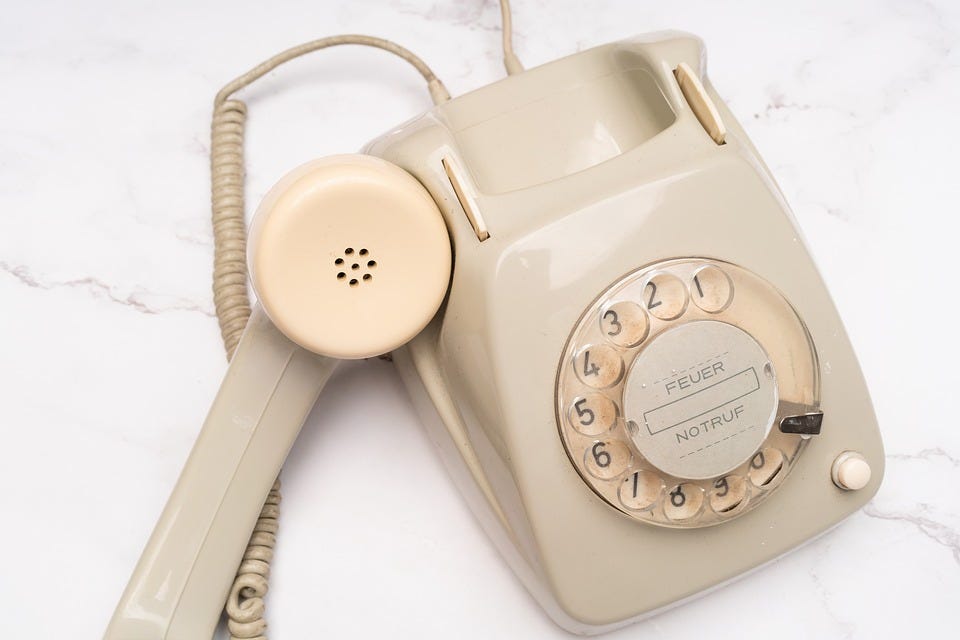

I imagined my mother sitting at the kitchen table as we spoke, the coiled phone cord as long as a transatlantic cable dangling between the beige phone with the rotary dial on the wall and the handset held to her ear. I can summon the memories of every detail of that room with ease — my mother’s cup of tea in her favourite porcelain tea mug resting on the Formica kitchen table; a small bookshelf brimming with cookbooks; the counters messy with the accoutrements of a passionate cook; the light tile floor; and her plants, some flourishing and some she was nursing back to life, hanging from macramé holders in front of the patio doors.

I knew that room down to the last spatula with the broken white handle in the messy top drawer beside the kitchen sink. If it was Wednesday, she would be perusing the grocery store flyers spread out on the kitchen table and deciding whether there were better deals at A & P or Loblaws. In the end, she shopped at both to get the best bargains.

My daily call was a casual chit-chat about what she was cooking or the visit of her grandchildren, my sister's sons. She wanted to know how my children were. I asked how she was feeling. “I’m fine,” she always said. I wanted to believe that she was. But I had become used to her keeping her feelings to herself.

The details I provided were equally superficial. “Yes, the kids are fine. No, I am not tired.” She had cancer, and I wasn’t going to worry her about my concerns. Besides, neither of us had ever shared our problems.

"I love you," she said at the end of every phone call.

“I love you, too.” Done. Phone call complete. I checked the task off my to-do list in my spiral-bound notebook.

She remained an enigma to me all her life. The distance between us was as far as Montreal, where I lived, to the village in Poland, where she was born. Whatever her story was, my mother guarded it to the end.

We never spoke about her childhood or how the family managed when her father was killed and she, the eldest, was only eleven. I still have no idea how much schooling she had. I knew, with the keen instinct of a child, not to ask. I never asked if she had been afraid doing forced labour during the war on a munitions factory assembly line in Germany, one of millions taken from their homes to feed Hitler’s war machine. To this day, I wonder if the trauma of that experience was the reason for her reticent silence. She did not tell me what it was like to arrive alone in a new country. She never mentioned the house in Westmount where she was required to work for one year as part of a government-sponsored immigration program for displaced persons —DPs as they were referred to — or acknowledged that it was a block from where I lived when she visited me.

She did not share if caring for her three children ever seemed too much for her. Although, she did confide once that sometimes she wept because she was so exhausted at the end of the day. This was a rare glimpse and admission that not everything in my mother’s life was what it seemed, and her burdens were heavy. I did not tell her that most days, I drowned my exhaustion with two or more glasses of chardonnay.

My mother did not talk about her health either. Within four years, the cancer had spread and was exacting its toll. On my visits home, I could see the weariness on her face. There were chemotherapy treatments and hospital stays for another four years. During her final weeks, she received palliative care, and my sisters and I came to help our father, taking turns being by her side every day in the hospital. Still she carried the burden of her illness silently, just as she had carried all her burdens.

My mother died eighteen years ago, and I still experience her presence. I have never felt my father’s presence since he died or anyone else’s, but I do hers. The first time was about five years after her death. I was driving through a busy intersection when someone ran a red light, and we nearly collided. I heard her sharply call my name, “Alinka” the Polish diminutive of my name that she always used even if we spoke in English, as if to reassure me and say everything was okay, although it was a very close call. And there have been other times when she has been there.

I know these are called bereavement hallucinations and are the realm of grief counsellors and psychiatrists. People can sense the presence of a loved one who has died, particularly during periods of intense grief, but they do not feel like a hallucination to me. She is simply present at unexpected moments. Her presence is a message about the enduring nature of motherhood.

While my mother remains a puzzle I will never complete because I don’t have all the pieces, I now realize she accomplished everything her heart desired when she started her life over in Canada. She did not want me to know or carry forward the emotional trauma she had survived. A fresh start in Canada meant that it was not passed down. Why did I not understand my mother’s silence about her experiences and the expectations she projected on me for what they were?

They were the hopes of every immigrant mother that their child will have an easier life, a safer home or more opportunities than they did.

It doesn’t seem possible that you can get to know a person better after they are dead. I have spent almost two decades since my mother’s death, and just as long before, trying to understand who she was. Because we change when something comes along to shift our perspective, we have a new capacity to get to know a person or see them differently. It has taken me a lifetime to realize I received an extraordinarily fortunate life from her. She guarded her secrets because sharing them would not have served her purpose.

I would give anything to talk to her again, one last time, to tell her I have learned that not all burdens are mine to carry alone. I also wish she had let me hold her burdens for a while.

Another beautiful and poignant essay, Alice. It reminds me that there are no final conversations, only interrupted ones, with much left unasked or unsaid. As for bereavement hallucinations, they aren’t really the domain of counsellors or psychiatrists; they are the normal property of grief and loss, not to be pathologized but rather to be recognized as transient sensory fragments of enduring connection.

Touching and resonates…”She guarded her secrets because sharing them would not have served her purpose”.❤️