Josie had never been on an airplane. At fifty-something, she'd never ventured beyond the familiar borders of Quebec and Ontario. So when my colleagues and I were tasked with taking our dedicated, soft-spoken secretary on her first field assignment to a developing country, we had no idea we were about to see our work through completely fresh eyes.

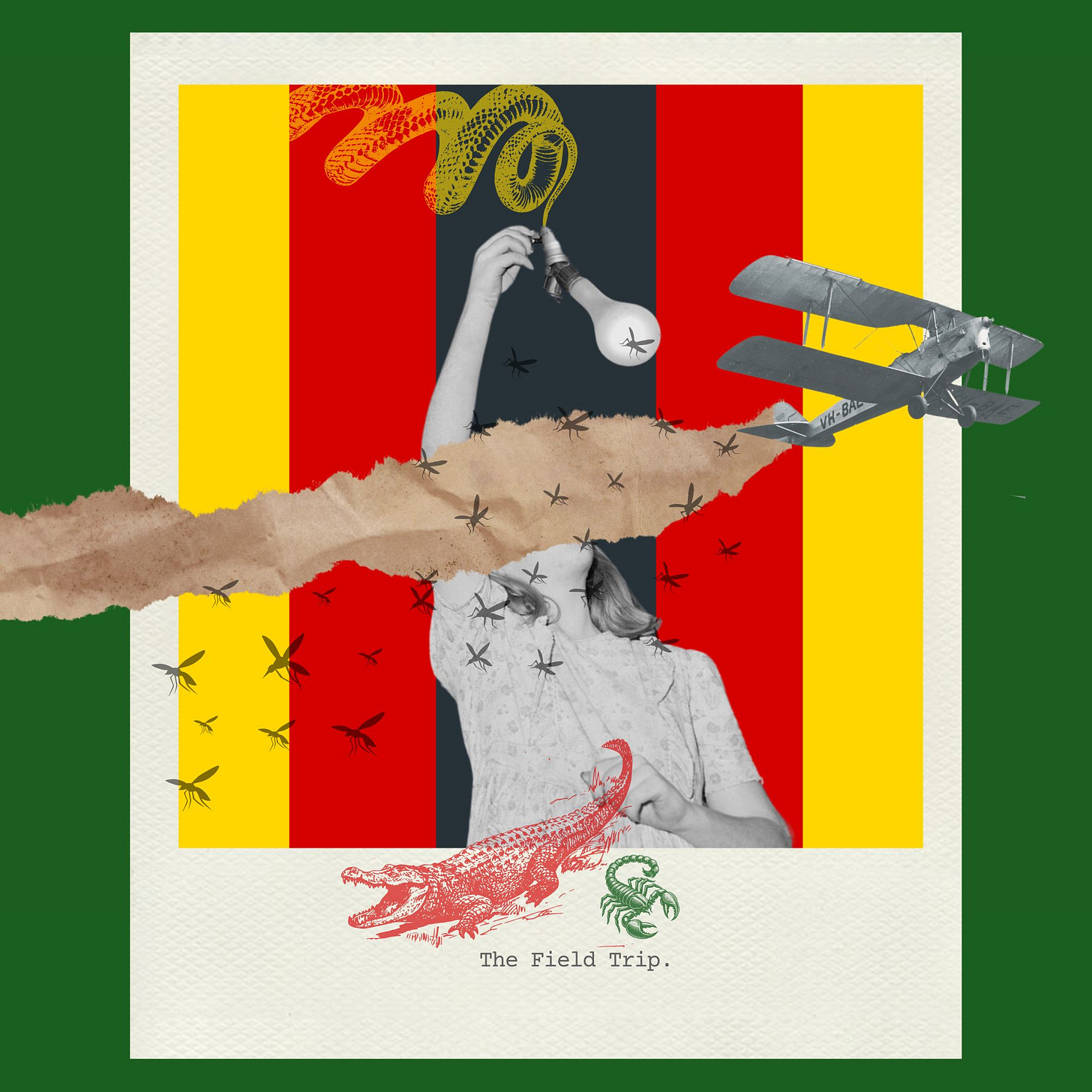

While I can only imagine what Josie made of her first flight and the bustling streets of Harare, the real story begins when we left the capital of Zimbabwe behind. We drove south into territory still scarred by civil war—land where thousands had died just years before. Roadside signs warned 'DANGER: LAND MINES' in bold red letters. We drove past them without a word, as casually as we might pass a speed limit sign back home.

At our one tourist destination, the Great Zimbabwe Ruins, the ancient stone structures and bleak hillsides created a sinister atmosphere. There were no other visitors, just the usual hordes of baboons. The aggressive males would charge and screech in our direction and saunter away.

When nature called, we headed to the concrete toilet block—a grim little building with stand-up stalls that were, mercifully, cleaner than expected. As we approached the entrance, I spotted a scorpion pressed against the doorframe, its tail curved and ready. 'Oh, just step around that,' one of my colleagues mentioned casually.

We visited several villages where the Canadian International Development Agency had provided assistance. The children, more grey than black due to lack of water for washing, surrounded us and grabbed our hands. To thank Canada for water, latrines, tools or other improvements to their lives, the villagers insisted upon gifting us a precious live chicken and sharing a sour-tasting pot of beer. We each took a mouthful of the latter. We left money with the chief for the chicken which was discretely returned to the village.

Near the equator, the sun sets by 6 PM, and we needed to reach our compound before dark. We arrived around 4 PM to temperatures in the 40s Celsius and oppressive humidity—typical conditions near the crocodile-infested Limpopo River that forms Zimbabwe's border with what was then apartheid South Africa.

We were tired, dust-covered and thirsty. Had we properly prepared Josie, including for the intense heat? She had had her shots for any number of potential diseases and been briefed about malaria-carrying mosquitos. Her long-sleeved shirt was buttoned up, her pants were inside her boots and her hat covered most of her face. Under the brim, she was ruddy but still smiling. No point to suggest she roll up her sleeves; there was no air.

The manager showed us around the spartan outpost. There was a small dilapidated pool half filled with slimy water. It was suggested that we not swim in the evening due to snakes. Zimbabwe is known for deadly snakes. We wondered what Josie might be thinking, but nobody commented.

As we were having a refreshment at the bar, a Crocodile Dundee lookalike sauntered in. He smashed down a machete into the wooden bar and demanded a beer. We all flinched but carried on talking. Although this movie character wasn't typical, there were a few such mavericks.

Our accommodation was a utilitarian concrete blockhouse perched above the river—each sparse room equipped with a metal bed, washstand, chamber pot, and single dangling light bulb. Outside each door sat a lonely chair where you could catch what little breeze there was and watch the wildlife below. In the murky water, crocodile eyes and snouts drifted like floating logs, patient and watching.

When we opened Josie's door, a cockroach scurried under the bed. No point switching rooms—they all came with these uninvited roommates. After unpacking, we gathered for dinner and talked shop about the day's projects. Josie listened quietly, saying little. Back in our rooms by 9 PM, the generators shut off and plunged us into a darkness so complete it would terrify any city dweller. I wondered if Josie had remembered her flashlight.

After a hearty English breakfast, we toured the grain research projects, then endured five hours of rutted dirt roads back to Harare. We collapsed gratefully into the air-conditioned luxury of our hotel.

Over dinner, we finally asked Josie what she'd thought of it all. In her quiet, French-accented voice, she delivered her verdict: she'd admired the projects, but thought we were completely insane. Land mines, scorpions, snakes, baboons, crocodiles, cockroaches, machete-wielding cowboys—we'd treated it all like a stroll through the park. She'd only pretended to drink that village beer, had never been so terrified by heat, and had spent the entire night fully dressed by her door, ready to run. The experience would stay with her forever, but she was sticking to headquarters, thank you very much. We laughed until we cried—and realized we'd never see 'the field' the same way again.

Entertaining and well-written story. Josie was very brave not to screech, scream and scram as I would have.

What an experience for Josie. Don’t blame her one bit!