Joseph, our departmental messenger, was a gold medal contender in the swivel chair sleep Olympics, during my tenure in the mid-1990s at the African Development Bank, in Abidjan. Mondays to Fridays, during office hours, he could reliably be found slouched in his shabby black swivel chair at the end of the corridor, snoring gently.

Joseph’s job, when not in sleep training, was to deal with the numerous documents that were constantly flying from one office to another, to make photocopies, and to ensure the copy machines were full of paper.

A seasoned bureaucrat, Joseph always knew to be available for any tasks given to him by the Director. The lower down staff were, the less chance of Joseph making their photocopies or delivering their documents. Staff learned that it was easier to do these things themselves. Joseph also knew that the secretaries hated photocopying, a task that they consider to be beneath them. He made sure to stay on their good side by making their copies.

And then Joseph departed on vacation. Secretaries were crankily making their own copies. Within a day, all of the photocopy machines on the seventh floor where my office was located were empty of paper. A crisis loomed.

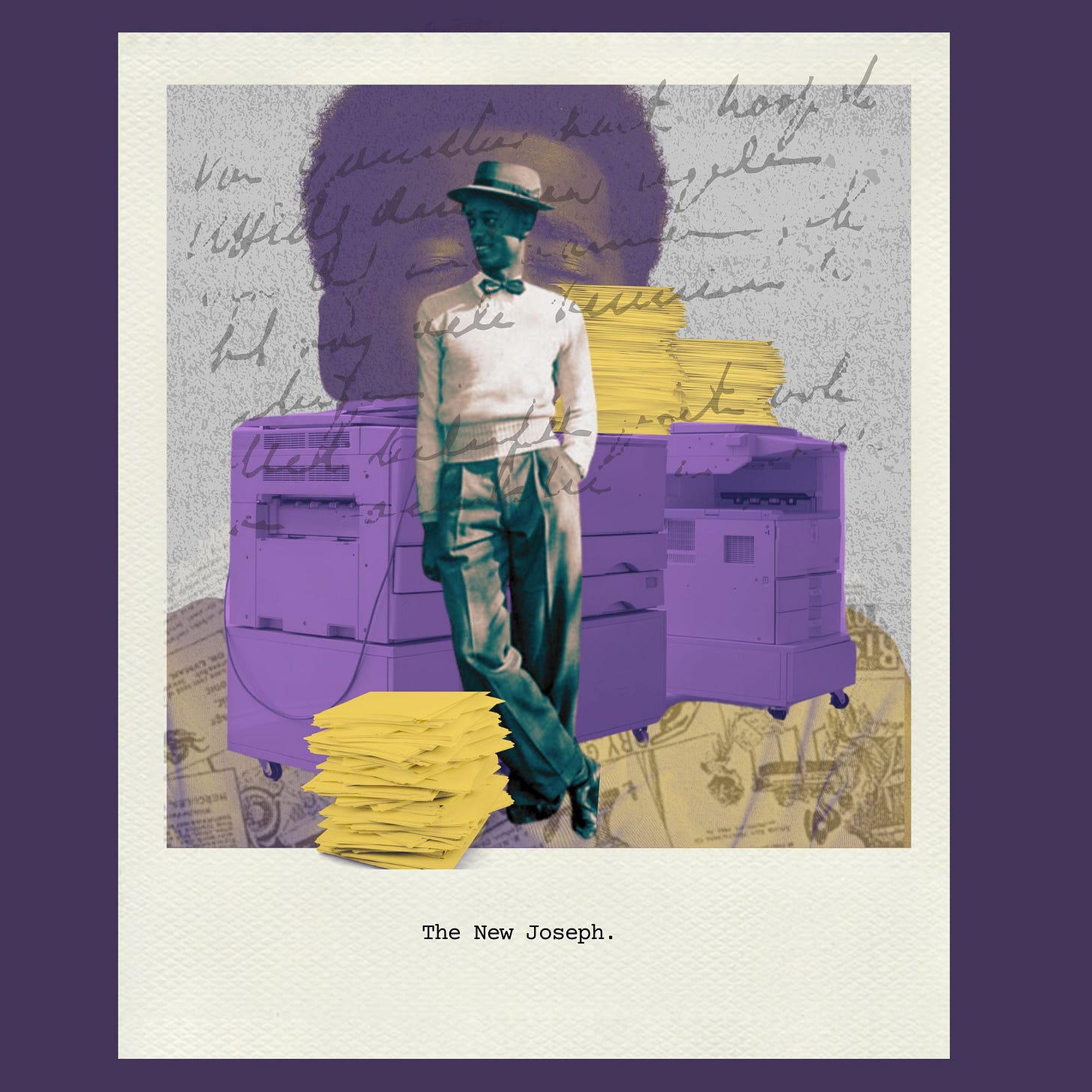

A few days after Joseph’s departure, a tall Burkinabé (from Burkina Faso) showed up. He sat in Joseph’s swivel chair, but he was awake! He was ready to work. The new Joseph was called Ferdinand. Everybody assumed that HR had sent him.

Ferdinand was a good worker, quiet and efficient. His soft voice was barely above a whisper; sometimes I strained to hear him. Ferdinand moved quickly and quietly through the corridors like a cat. He owned two pairs of pants, one green, the other purple, which he wore with sparkling white shirts. Ferdinand came to work daily in one of these two pairs of pants, impeccably pressed and made shiny by frequent ironing.

He made photocopies, ensured the copy machine was always full of paper and ordered new ink cartridges when the old ones were empty. No more running between floors to find a working copier. Ferdinand delivered files, distributed documents and ran personal errands for staff for tips. Everyone was impressed with Ferdinand’s work ethic. After Joseph returned from vacation, Ferdinand stayed. He had created his own job. Nobody asked why he didn't leave. He was invaluable. We all chipped in to give him and Joseph a cash gift at Christmas. Things ran smoothly.

Two years after Ferdinand first appeared, there was change in the air. All staff were issued shiny new electronic ID cards, which were required to get into the building. Ferdinand started to show up late, then not at all. That's how we learned that Ferdinand did not actually work for the organization. In the two years he had been working in our department his status had never been verified. It turned out he was just a guy who walked in off the street and got a lucky break. He probably knew somebody inside who tipped him off about Joseph's vacation.

Under the new system, as he was not an employee, Ferdinand was not entitled to an ID card, and it was impossible for him to enter the building to work at a job that never existed.

Ferdinand had been making a good income for several years from the tips he got from doing errands for professional staff. Now his source of income was gone.

Joseph got an early retirement package. Email was the new way to deliver documents. It looked like the tradition of the messenger, sleeping or awake, was no more. Several months after he stopped showing up for work, I ran into Ferdinand on the street. His purple pants and crisp white shirt glistened in the afternoon heat.

“Bonjour Ferdinand. Ça va?” I asked.

Ferdinand shook his head. I saw the sadness in his eyes. I reached into my purse and handed him some bills.

“Je vous rembourserai Madame. Merci mille fois.”

I knew I would never get the money back. A few weeks later, I left Abidjan for good.

I never saw Ferdinand again.

Still pondering this story as I see it on many different levels of metaphor. In my consciousness, the ingredients of this story have not yet cooked enough into a final stew.

This is a lovely story. Both Joseph and Ferdinand are fleshed out compassionately and vividly.