In the summer of 1964, my Uncle Frank came home to Dublin after living for a half-century in America. No one had heard from him in 20 years. If we thought of him at all, it was to presume him dead.

At fourteen, I was not enthusiastic about meeting some old Yank. He wasn’t even my uncle, but a great-uncle, one of my grandmother Maisie’s six older brothers.

All she had of him was a faded photograph in a tattered album. The photo showed a skinny teenager with a mop of curls sitting outside a farmhouse in a pony and trap. On the back someone had written: “Frank McCourt, headed to America in the year 1913.”

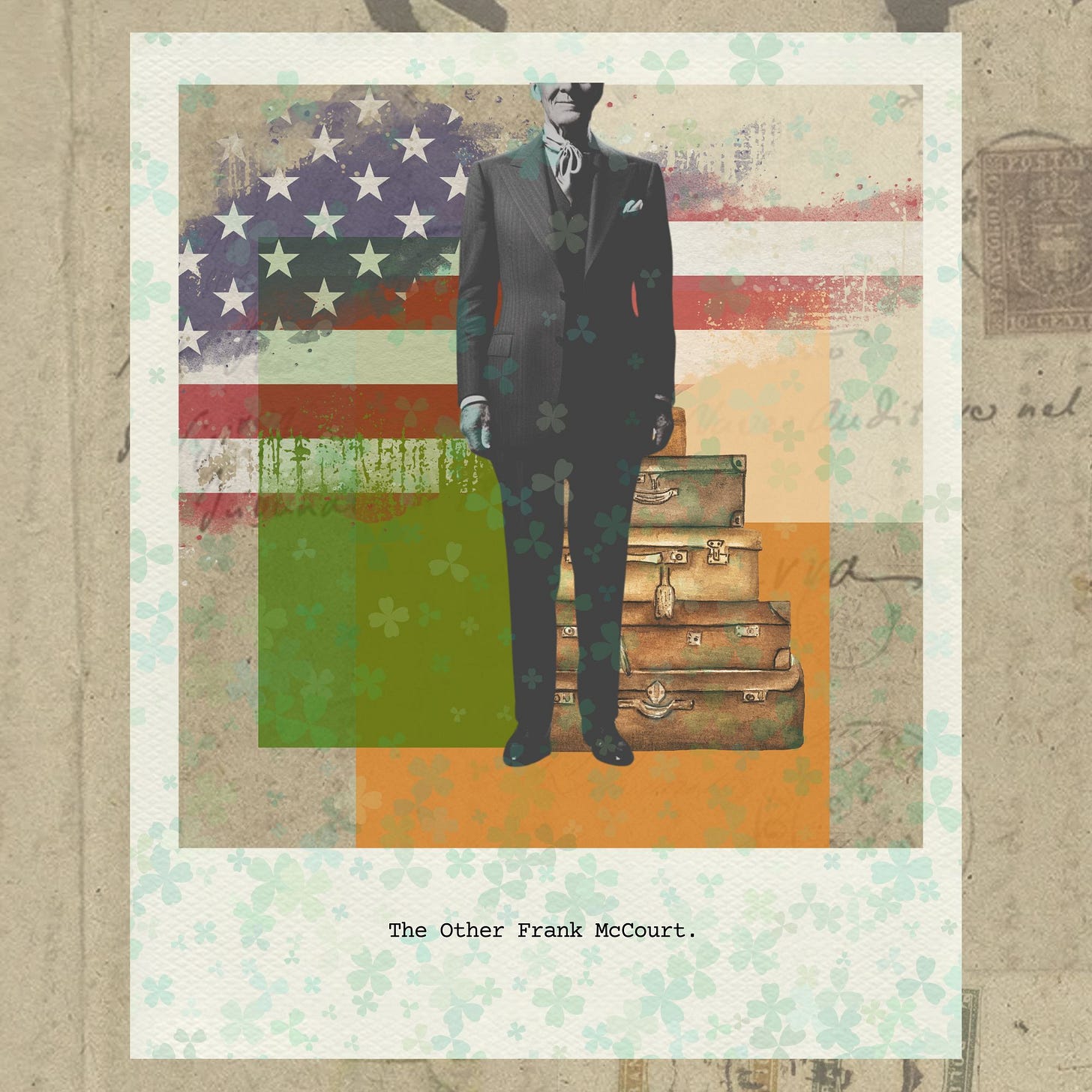

I should point out that Uncle Frank was not related—as far as we knew—to another Irish man of the same name who won a Pulitzer for Angela’s Ashes, a harrowing, very funny memoir about growing up in abject poverty in Limerick and escaping to New York in his 20s.

When the letter arrived from her brother asking if he could board at her house—he would pay, of course—Maisie was caught off guard. But, as was her way, she soon rallied and prepared her home—and my Grandfather Jimmy—for the arrival of a man who was essentially a stranger.

In those days, many families had aging American relatives who wanted to end their days in Ireland. But we had mixed feelings about homecoming Yanks. We complained about the loud, brash and demanding American tourists who were, nevertheless, a mainstay of our economy. On the other hand, we were unabashedly proud of the wealth and success of families like the Kennedys. Practically every home had a picture of JFK on display. Uncle Frank, we were pleased to learn, was not an Ugly American, but a gentleman who, although not rich like the Kennedys, had made a good living as an executive in insurance.

I was part of an informal welcome party the day Uncle Frank arrived from Chicago. Me and my grandparents and my Aunt Peggy, just eleven years my senior, greeted him as he emerged from the luggage-laden taxi. Pausing on the sidewalk, he leaned on a brass-handled walking stick and greeted us with a sweet, uncertain smile.

My first impressions were that he looked like Fred Astaire and that he was the cleanest man I’d ever met. He had the same slim build as the famous dancer, the same grace in movement. He wore a silk cravat tucked at the neck of his navy-blue blazer, and a crisp white shirt with gold cufflinks. His leather brogues were polished to a shine.

Peggy and I carried Uncle Frank’s suitcases up to the third floor. He had been assigned the warmest part of the house because Maisie knew that Americans found it hard to get warm in our damp, chilly climate.

At a party in his honour that first week, Frank entertained us with tales of his adopted country. He spoke with wit and ease in a way that reminded me of Hollywood legend Humphrey Bogart. He told of the colourful characters in his South Chicago neighbourhood, which made me think of Harry the Horse, The Lemon Drop Kid, and Madame La Gimp, part of a cast of characters that populated Damon Runyon’s wonderful stories of New York. I had recently picked up his “Guys and Dolls” collection at the public library.

Uncle Frank smoked Camels in a cigarette holder, drank bourbon on the rocks, and had once owned a yellow Corvette. To me, he was America, the land of cops and Capone, hot dogs and hot rods, Marilyn Monroe, and a handsome Irish-American president with a stylish wife. And teenagers who drove their own cars and made out in the back seat or on the beach. In Dublin, if we did it at all, we did it in fields and in alleyways, all the while freezing in the perpetual rain.

In the evenings, Frank would sit almost on top of the little gas fire in his room, while I sat on a footstool by his armchair, feeling special because I knew he liked my company. We would sip cocoa and eat cinnamon toast.

On his dressing table, alongside his silver-backed hair brushes and his manicure set, Frank placed a framed photograph of a pretty woman, perhaps in her mid-thirties, and a boy of about ten laughing up at her. The woman, Frank explained, was his Polish wife Jodi. She had died of a stroke two years before he left Chicago. Their son, Paul, had died of leukemia at fifteen. Frank said that he had left America because he had run out of family there.

And what of his rediscovered family in Dublin? Maisie and he shared a lot of family quirks. They had the same sense of humour and read the same novels. They enjoyed reminiscing about growing up on a dairy farm in Offaly.

Frank and my grandfather were very different men, but they got along well. A butcher by trade, Jimmy cared little about how he dressed. He liked to throw on an old apron and cook up the lesser-known meats, likes sheep’s head, calf liver, beef heart and sweetbreads. Frank, more of a vegetable man and fastidious to the point of neurosis, used to peer around the kitchen door, screw up his face in mild disgust and say “Jesus Jimmy, the blood, the grease.”

Frank and Aunt Peggy, who was very pretty, had an innocently flirtatious relationship. He would compliment her on a new dress or hairstyle. She would giggle and bat her mascaraed eyelashes at him.

Frank died of pneumonia three years after he came home to Ireland. He was the first dead person I ever saw. His decline began when he started drinking more. His slim face became skeletal. His silver hair brushes were put away in a drawer. His stories dried up.

Years later, I asked my father what he remembered about Frank: “He was a lovely man, but he should never have come back here. It was too late. He never settled. He hated the cold. He missed Chicago. He pined for his old friend Robert Ryan (an old movie actor and civil rights activist friend seen with Frank in another photo on his dressing table).”

My most vivid memory of Uncle Frank was the day we took the train to Skerries, a quaint seaside town outside of Dublin. We were there to spend the five pounds I had won in a newspaper competition—something to do with words—I can’t recall what exactly. Uncle Frank said we need not wait for the cheque to come. He would lend me the money, and we would spend it on high tea in the old hotel that overlooked the sea in Skerries harbour. I took his arm when we left the station, and we strolled along the promenade. We sat by the window in the Savoy. We drank Earl Grey tea from china cups. We ate cucumber and watercress sandwiches from the top of a silver three-tiered stand, scones from the middle tier, and slices of a Victoria Sponge from the bottom tier.

On the train home to Dublin, I remember Uncle Frank telling me that I was good with words and that he hoped I would be a writer someday. When my prize money finally showed up in the post, he would not let me repay him.

He was ever the gentleman, my old Yank.

Paula, I could hear your voice as I read this piece. Thank you for sharing him with us. He was so right about your facility with words so early on and now in full bloom.

Wonderful writing, Paula. You bring him to life for us.