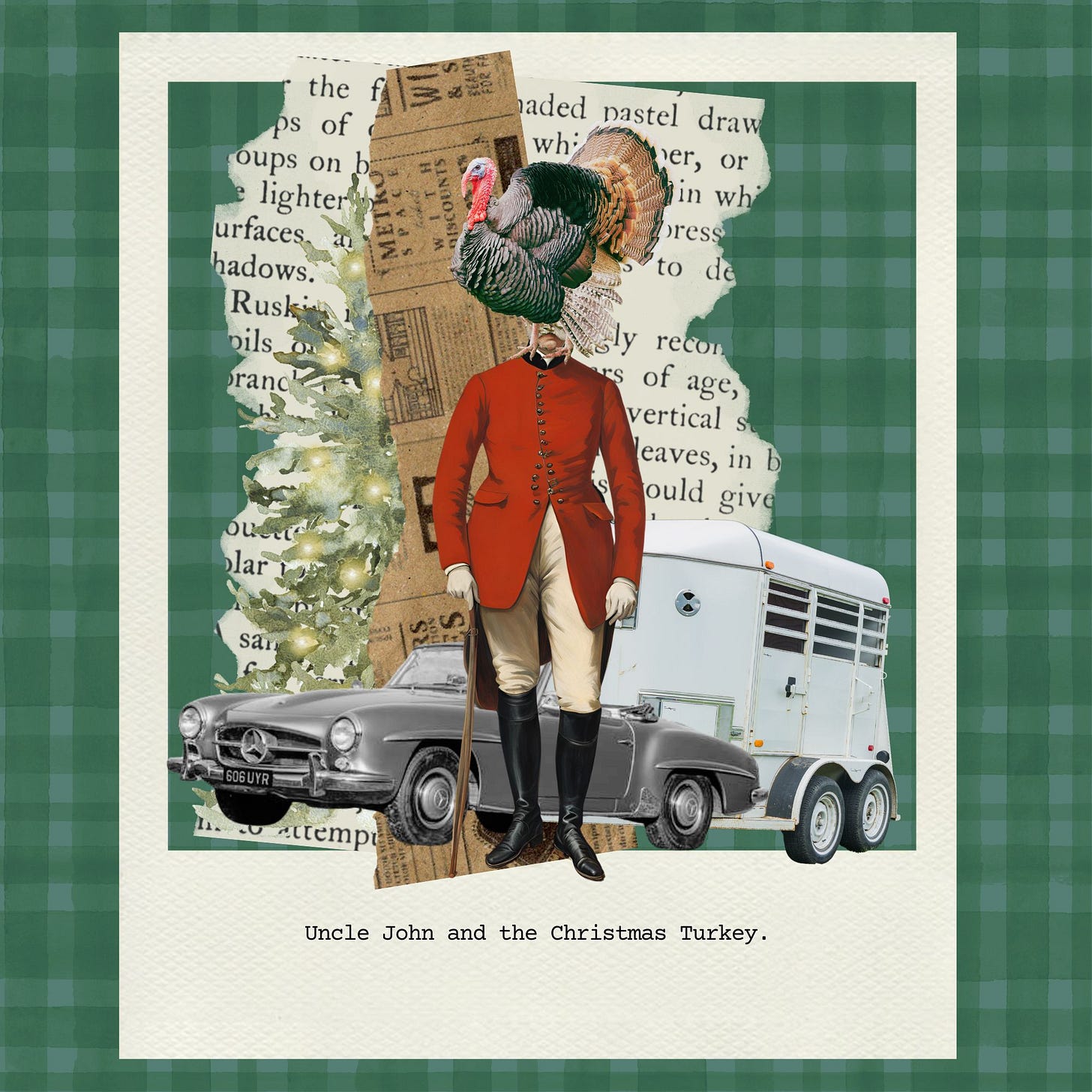

My abiding image of Uncle John is of him emerging from his silver Mercedes outside our house one Christmas Eve, carrying the biggest turkey we seven siblings had ever seen. Its wattled neck dangled down Uncle John’s red riding jacket. The jacket was paired with jodhpurs and a black riding helmet.

Hitched to the back of the car was a horse box containing Uncle John’s horse, Blaze, so named for the white marking down the centre of his noble face.

A small crowd of neighbour kids, eyes wide at this splendid, unexpected sight on our narrow Dublin street, gathered around to marvel at Blaze, who stared back, unperturbed. The bolder kids peppered John with questions. Hey, Mister, where’d you get the horse? Where’s his nosebag? How fast does your car go, Mister?

My brothers, sister, and I preened at the attention our family was attracting. Few families in our working-class neighbourhood had cars in the 1950s—and certainly not anything as grand as Uncle John’s German-engineered automobile. The only horses we knew were the unbridled ones that pulled the caravans of the travellers, an itinerant nomadic people who, for centuries, have roamed from place to place around Ireland.

I admired Uncle John because he was unconventional—a character. Some in the family considered him a dilettante. But in my eyes, he was a romantic risk-taker. No one else I knew rode horses for pleasure. No one else swam year-round in the freezing Irish Sea. No other uncle drank a dry martini (or two) before dinner every night—the other uncles were strictly Guinness men.

And nobody in my circle could claim that their uncle had, in the late 1960s, opened a club in Dublin modelled on the legendary Cavern in Liverpool where the Beatles got their start. Uncle John sent me an honorary membership to Club-a-GoGo when I turned eighteen. I still have it somewhere. I saw Gerry and the Pacemakers, Dusty Springfield and Cat Stevens play there. It was the year I wore the mini-skirt and thigh-high white boots that drove my father up the wall. Uncle John was way more with it than my dear old Dad. John’s four teenage daughters (my snooty cousins) were allowed to work at the club on weekends, flirt with older boys, and get the autographs of rock stars.

I met my “starter” husband at the GoGo. Joe was with a group of lads standing by the stage. He was wearing crutches. As I passed, he grinned at me and said something I could not hear, but which made the others laugh. Turns out he had crashed his Harley Davidson the week before and had broken his ankle. We were married two years later.

Joe was a bad boy who tried his best to reform, but he continued to see other women during our 10-year marriage. I had no idea how to cope. When it ended, I was left with little money but had held on to my three children. My sore heart was bruised but not broken. My second marriage, now in its 40th year, seems to be working out.

Looking back, I may have been attracted in part to husband #1 because he reminded me of Uncle John, another charming philanderer. John kept several mistresses over the years. He paid for love nests for at least two of them that I know of. He was surely the only one of my many uncles likely to have chanced that type of unconventionality.

Despite his affairs, his wife stayed with him. I’m told that they struck a Faustian bargain early on. He would provide enough money for his wife—rumoured to be more in love with shopping than with him—to live in material comfort. She would turn a blind eye to his dalliances. As far as I know, they both honoured the bargain until he died, leaving her a small fortune. She wore a mink coat to his funeral, and someone pelted it with an overripe tomato.

And as far as I can tell, the one woman John loved unconditionally—apart from his daughters whom he spoiled rotten—was my mother Maura, his big sister. One demonstration of that affection came in the form of the turkey he bestowed on us every year for our Christmas dinner. Before he acquired wealth and luxury cars, he would deliver the bird by motorbike.,

I don’t remember Uncle John ever letting us down, but my mother never knew when precisely he would show up. So, each year, we would wait with bated breath for his arrival. Sometimes, it would be a few days before the holiday; other times, he left it to the last minute and would come late on Christmas Eve.

Usually, the turkey would come prepared for the oven. Occasionally, however, as was the case the year of the horse box, my mother would have to stay up into the early hours on Christmas Eve, chopping off the head of the big bird (15-20 lbs), pulling out its innards, saving the giblets for gravy stock, using pliers to pluck out remnants of its feathers. She did all this with the skilled detachment of a surgeon. My squeamish father would wait until this operation was complete and then emerge from hiding to wrestle the big stuffed bird into the oven and prop the door closed with a metal chair for the four or five hours of roasting time.

Each year, the first toast at our Christmas dinner table was to our Uncle John, procurer of large family-sized turkeys, debonaire night-club owner, and all-round good fellow—mostly.

Ah. Paula. What a gem.

A terrific story, Paula; we can sense the wide-eyed wonder and appreciation of your child self. Let's hear it for the helpful aunts and uncles out there! My own helped me buy this house I've lived in for nearly forty years. Wouldn't be here without them. Merry Christmas to you all.