I’d like to think that my babushka balled her calloused fingers into a fist and punched the priest right between the eyes when he leaned in and whispered that she’d have to pay him if he was to sign the papers authorizing her passage to Canada. I’d like to think that when he was lying at her feet, his black Oxfords muddied and a stream of blood dripping from his nose, she stuck a pen in his hand and made him sign.

But what I’d like to think isn’t what happened on the day before she walked across those potato fields, probably thinking about her two brothers who had been struck by lightning and killed while they were stealing spuds for supper, got on a ship, and arrived ten days later at the Port of Halifax.

She stepped off the ship, stood in line with hundreds of other men and women who had left their own fields behind, and signed on the dotted line signifying her entry to Canada. While my babushka was not in the market for salvation, she did accept the ivory dress, a bouquet of plastic carnations and white shoes from an officer of the Salvation Army so that she could have her photo taken with her new husband, who she had met only once in the old country.

“I thought they were sending me your sister,” my grandfather apparently said, stamping out his cigarette.

“Well, you got me.”

I’ve made that response up as well, but really, what else could she have said?

Snap. The photo was taken and my grandparents returned the borrowed dress, the shoes, the suit, and the fedora. Their photograph was sent to the old country as proof of the wedding, and they boarded a train for Montreal where my babushka began working in the schmatta industry counting buttons and my dyedushka began working in a foundry where his lungs became darker by the day. Soon my mother was born and by the time she was five, she’d learned how to make herself breakfast and lunch, lock the front door on her way to school, ignore the teacher who told her your father needs to speak the Queen’s English, be gracious to the prostitutes who lived at the corner, and feed the catfish that her mother brought home from the river.

“Mama would get on the bus equipped with a stick, a string, a blanket, and a bottle. On the way home she’d sit with the catfish cradled in her arms and feed it from the bottle, ignoring the stares from the passengers.”

“Mum!” I’d say. She often told me these stories when we were at my aunt’s dacha where we would do the dishes together in the evening.

“It’s true. I couldn’t take a bath for weeks because the fish lived in the tub. When it was big and fat, she’d slaughter it and make a big soup.”

“Mum!” I’d say, ready for her to tell me about how her parents saved money and hid it under the boards in the kitchen floor, how she would get ends of smoked meat from the local deli at the end of the day, and how she would wash her father’s feet when he was tired.

“It’s true. Remember the catfish you caught when you were little that became soup?”

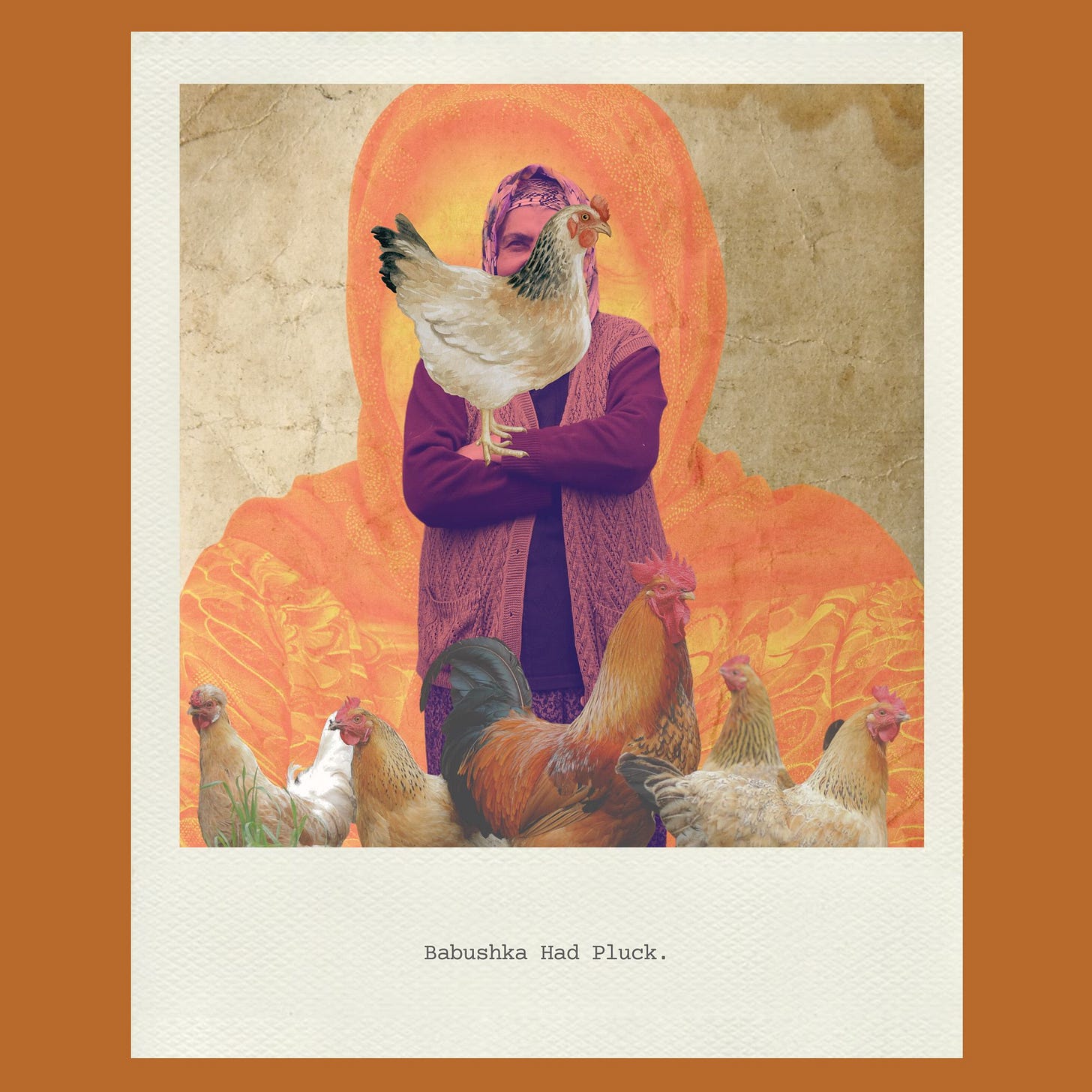

And I do. I remember not being able to eat the soup because of the whiskers floating in my bowl. I was in elementary school when my babushka gave up fishing and took up chicken farming in the basement of her apartment building. She’d go to the market and talk to the chickens in the cages until she found one she liked. She’d walk it home on a leash, take it to the basement and feed it for weeks. Because the windows were open, I’d occasionally hear her singing to the chicken.

Kalinka, kalinka, kalinka moya

Berry raspberry in the garden, raspberry of mine

Kalinka, kalinka, kalinka of mine

“When the chicken was good and fat, she’d pick it up, sit it on her lap and croon lullabies until it was sound asleep, snoring so loudly the neighbours would complain.”

“MUM!” The story becomes more embellished every time I hear it and no doubt, I have enhanced it as well. Mostly my mum cries when she remembers her mother, my babushka.

“It’s true. And then she’d snap its neck, pluck it, clean it, and store the feathers in pickle jars. Don’t you remember how good that chicken was?”

I do. I also remember arriving home at lunch and finding my babushka making borsht in our kitchen but what I really wanted was soup that came out of a can, fish that was breaded and shaped into neat little sticks, and a small tv on the counter like Cindy had where she watched The Flintstones at noon.

One day in grade six I was coming home for lunch and when I turned the corner, I saw my babushka shuffling towards our house led by her black oxfords, her bulging bags of rye bread and her head wrapped in an orange kerchief. I pretended not to see her, turned to Susan or maybe Cindy and walked the other way, avoiding the introduction. She can’t speak English anyway, I might have rationalized, but fifty years later I still feel the shame that covered me like a light film of sweat. It took decades before I realized how proud I was of that catfish fisherwoman, basement-chicken-farmer, old-country-mail-order-bride.

Eventually my babushka was promoted at the garment factory, became a seamstress, and joined the newly formed union which meant that she had time to eat lunch, that there would have to be windows in the room where she sewed and that when she finally retired, she’d still have some income. She moved to a building without a basement but with plum trees in the garden, which she loved. I was in high school and would visit her once a week and sit with her while she made plum pies and apple pies and crispy cookies that she deep fried. We’d sit and peel the fruit, and she’d never say anything when I ate the pie dough, unlike my mother who would scold me and say I would get sick. Babushka would buy me fat steaks that she would fry in butter, she’d make pickles that we’d eat with our fingers, she’d boil up beef bones and scoop out the marrow, spread it on rye bread and sprinkle it with salt and when I slept over, she’d fry the rye bread in bacon fat and serve it with a spatula for breakfast. Years later in a fancy-shmancy restaurant, I ordered bone marrow that arrived on a too-big white plate in a puddle of broth. Where’s the rye bread? I wanted to ask.

By the time I was twenty-two, live chickens could no longer be bought at the market, walked home on a leash, and fattened up in basements. And by the time I was twenty-two, my babushka had forgotten how to use scissors. She didn’t realize that her dentures were her teeth and left them in a glass of water next to the pickle jars. It was days before we found them. She could no longer fry a steak, peel apples or make pancakes from a mix. But she sure loved chicken that came in a bucket, so we’d set the table with the fine china she’d collected over the years, licking our fingers and wiping our greasy faces with white paper napkins.

Just before I got married, I went to see her at her nursing home. I stood in the doorway, watching her sitting at the window. She was safe here, although my mother told me she had once arrived to find my babushka tied to a chair so that she wouldn’t wander off. I’ll strangle you, my mother told the manager, if this ever happens again. The cruelty of this gesture cemented for me that the path to hell is sealed by those who only mean well.

I looked at her sitting quietly and wondered what might be going through her head. Was she thinking about her sisters who she had only seen once when she returned to the old country, where she carefully removed the lining from her purse and handed out the dollars she had smuggled in for them? Was she picturing the curtain she’d hung in the middle of a room, renting out one half to a stranger so that she had extra money for eggs, butter, and milk? When she began wringing her hands, was she remembering the afternoon she found her husband still in bed, and how she shook him when he wouldn’t wake up? Could she hear her four-year-old daughter crying as she waved goodbye to her mother every Monday morning knowing she wouldn’t hug her again until Friday? Was she thinking about I Love Lucy and how she used to sit on the edge of the brown couch and laugh when it came on just before dinner?

She couldn’t tell me what was going on in her head, but she could smile and grip my hand when I told her my news.

“Babushka, I’m getting married!”

“Ba ba ba,ba ba,” she chortled.

And I laughed because I knew she understood, and then I sat with her and helped her eat

vanilla pudding. In this place that was to be her last stop, I hoped she could still picture the tree in her garden with its dark purple plums and taste the sweet red pulp of the sun-kissed fruit.

After we were married, my mother presented me with two pillows and two white pillowcases.

“They’re from Babushka; she made them for you just before dyedushka died and asked that I give them to you as a wedding gift.”

I held them and could feel how fat and plushy they were but it was only when I got home that I hugged them, that I buried my nose in them and thought about this woman who had crossed a potato field on foot, an ocean on an overcrowded boat to marry a man she had met once, and even though her grand-daughter had once avoided her, collected every feather anyway so that her Annushka would sleep well at night.

“These pillows are made from every chicken she raised, every chicken she crooned to, every chicken she plucked.”

“Mum.” I whispered.

“It’s true.”

Thirty years later, the little feathers in my babushka’s pillows are coming out. Sometimes

they poke me as I am trying to go to sleep; sometimes when I pull off the cases, they will flutter out, landing on my arm or leg, or on the carpet. And then I think of my babushka and remember the yellow box of Chiclets that was always in her purse, her bunioned feet stuffed into those black oxfords, her gnarled hands guiding mine along a line of fabric, her trip to the old country where she visited her parent’s graves, and how she welcomed stray cats with a bowl of milk. She was courageous, my friends have said. She never complained my mother likes to remind me. She was a lady my father will add.

Her Salvation Army wedding photo stands beside mine in a matching silver frame.

Soon after we were married, I served ossobuco at a dinner party. The table was set with fine china, my mother’s crystal and my babushka’s cutlery. I mashed the potatoes with lots of butter and cream, blanched the beans and poured the inky cabernet. We talked, we ate, we drank; it was a good dinner. In that moment between clearing the table and putting out cheesecake, I noticed that our guests had left their bones filled with marrow. I hesitated before launching; they watched in horror at how I sucked those bones one after the other, piling my plate with their leftovers. Better on rye, I told them.

Winner of The 2024 International Amy MacRae Award for Memoir

Beautiful story, thank you for this memory of your Babushka 🥰

Anna, you deserve that award and so many more. As does your grandmother. Oh how I loved this beautiful evocative honest piece of writing! Plum trees and pillowcases. And such love.