My mother smiled indulgently when I polished up my trumpet and travelled with my university’s Varsity Band to football games in other cities where we marched through the streets, wearing handsome caps and long capes in the school colours, blue and white. Bold and blaring. Virile.

Meanwhile, Mom was at home playing Beethoven sonatas. And when she taught me piano between football weekends, memories of splendid capes, caps, and trumpets faded away. We leaned forward side by side on the piano bench. My long fingers, inherited from her, tried to imitate hers. Hours of scales and finger exercises before the real music. Bach, Beethoven, Chopin; they lifted me from the planet I knew.

Thirty-five years after the marching band, soon after my father died, Mom was feeling very low. More than grieving, she was clinically depressed. We went to piano concerts to help her feel better.

She was in the theatre lobby waiting for me. At ninety-one, she had come alone by subway and bus. “I love my independence,” she said. “The only hard part was that high step up into the bus.

I took her hand, and we walked to our seats. The pianist played Beethoven’s Sonata No. 18. It was in my bones from childhood, Mom labouring over it, producing Beethoven’s stirring power, then his exquisite tenderness.

The last movement, the Presto, is meant to describe running horses, she said. In 1920, when she was fourteen, she had an after-school job playing it on the piano at the silent movies.

“I would sit just under the stage in the theatre and look up at the screen. If it was a love scene, I played Chopin. And if it was a Western and the horses were running, I played that movement.”

Her eyes shone. The memory of the notes swelled within her, squeezing out her depression until there was no room left for it.

She lived long enough that I could have the pleasure of caring for her, parenting my parent. The first time I put on her shoes, did up her buttons, cut her toenails for her, a deep, startling happiness filled me, to do for her what she had done for me when I was a child.

In old age, she kept her firm opinions. The most damning criticism she could think of was to describe somebody as crude. Or—just as insulting—ordinary. The flip side, her greatest compliment, was cultivated, or refined. And regarding music, sublime. I came to understand the weight of these words.

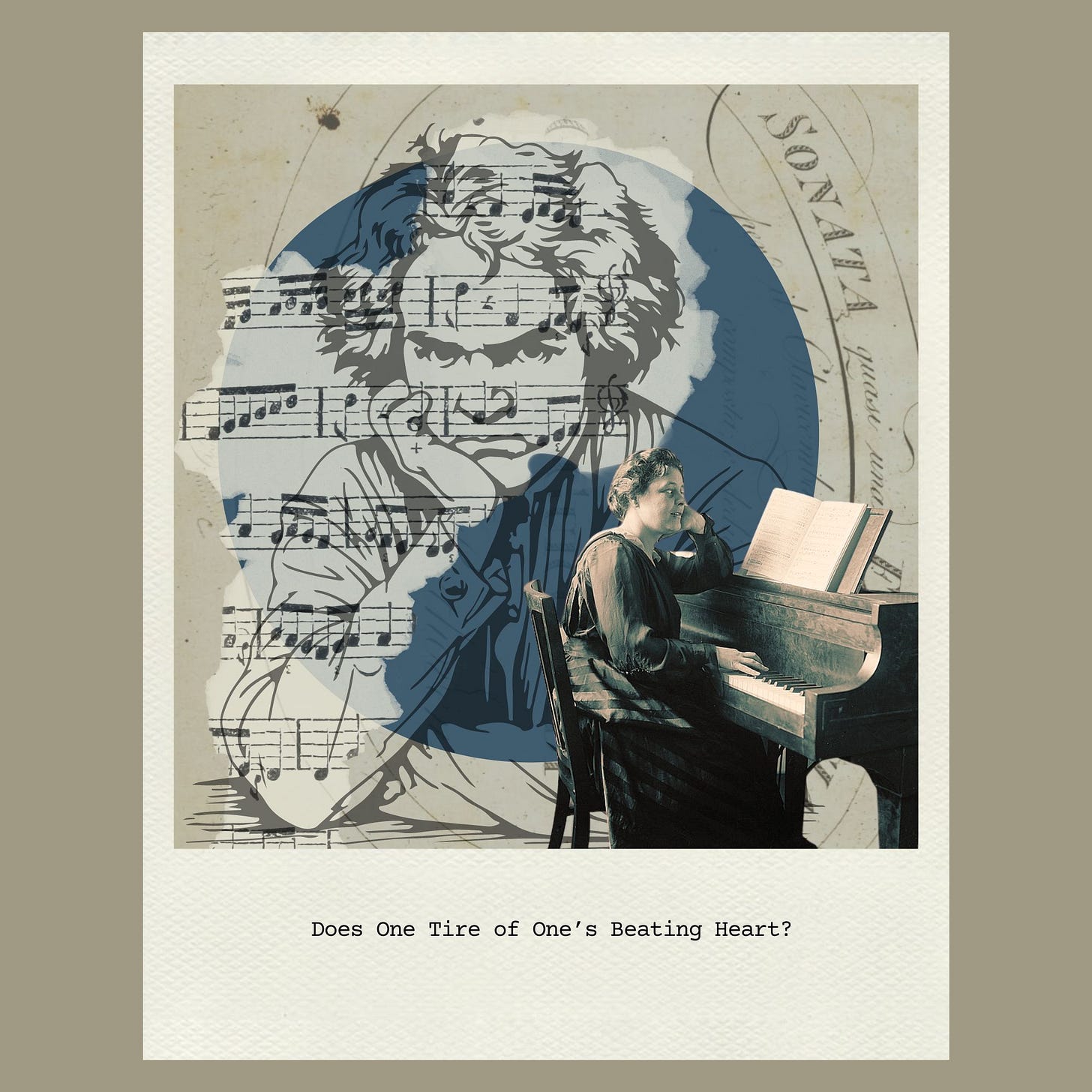

For her, the Beethoven sonatas were the peak of human aspiration and expression.

My kids asked me, “Why does Grandma play Beethoven so much?” When I told her that, she smiled.

“Somebody,” she said, “once asked Claudio Arrau, ‘Don’t you get tired of playing Beethoven?’”

I nodded, waiting.

“He answered, ‘Does one tire of one’s beating heart?’”

At another concert when she was ninety-five, we heard a piano song by Schubert. She closed her eyes, transfixed. Moved, she rested her head in her hands.

“That song was my favourite,” she said when it was over. “I used to nearly swoon when playing it.”

Swoon—nobody in my generation used that word. Yet I felt the bond between us.

There’s a rapture I’ve felt playing in an orchestra, singing in a choir. It’s unlike anything else. I took her hand: knobbly knuckles, ancient blue veins. Parchment skin.

The concert ended with a prolonged, standing ovation. It was going to force the performers to play an encore.

“I hope they don’t,” Mom said. I asked why.

“After that... there is nothing else.”

We walked slowly to my car, her feathery arm cradled in mine. “Sometimes you wonder what is the point of living,” she said, voice soft.

“Then you hear music like this, and you realize that yes, life is worth living.”

Eventually, Mom did tire of her beating heart; at age 102, it stopped.

I merge my car onto the expressway, sixteen lanes, eight in each direction. Looking ahead, at the side mirrors, rear-view mirror, gauging crazy movement all around me. Cars weave sharply in and out of lanes at 130 kilometres an hour. With the hypervigilance, a tightness grips my throat.

I crave the antidote. I turn on the car radio, and a station is playing a tender Beethoven sonata that Mom played at the silent movies and in later life at home. It envelops, surges in my chest. The tension in my throat drains away; I am drenched with music. I am somehow still alert to the complex traffic around me, but I feel a lightness now, pulled, like her, out of crudeness into the sublime. Singing aloud, loud, feeling the rhythms, lifting. Mending.

Sometimes, we search for our beating heart, and sometimes, it searches for us.

How wonderful that you had your mother for such a long and full lifetime, Peter. This is a beautiful tribute to her and to the power of music.

Wonderful, heartfelt memories, Peter. Beautifully written. I'm sure if she was with us today, she would find words other than "crude" and "ordinary" to describe Mr. Trump. Hugh