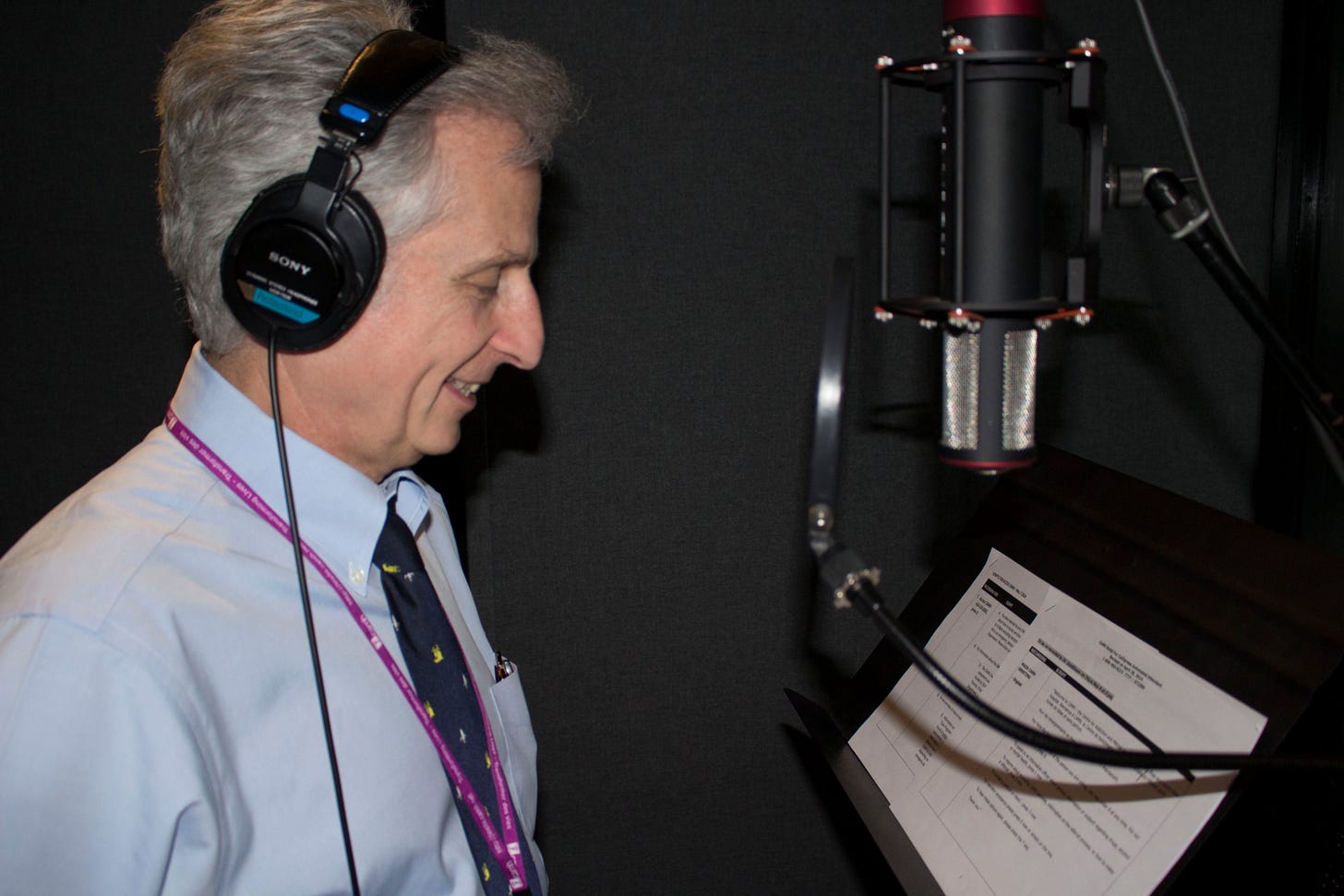

David as the voice of the voice mail.

For the past twenty-two years of the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health, referred to as CAMH by staff and patients, and for three years before that at its precursor, the Clarke Institute of Psychiatry, the recorded greeting welcoming callers and explaining options, in English and French, has had a consistent voice: mine.

It began in the mid-1990s when the Clarke switched from an old-fashioned live switchboard to a virtual Medusa of voice mail options. It was likely unusual for the Chief of Staff at the Clarke or the inaugural Physician-in-Chief at CAMH to fulfill this role. But the story behind it goes back to my childhood and possibly all the way back to Cain and Abel.

As the youngest of three children, I was a living and breathing plush toy for my sister, three years my senior, who ultimately translated her love of children into motherhood and a long career as a teacher. She pampered me until I was old enough to act as a security guard for her anxieties about possible intruders in our basement (there never were any, but I was her canary in the coal mine). My brother, six years older than me, played a different role in my life before he became a pediatrician and hospital leader. He served as a beacon for me to all that was ideal and desirable, and my wish to emulate him led to slavish devotion to and literal interpretation of his opinions and directives. This cult-like worship, fused with my complete gullibility, made it impossible for him to resist teasing, tricking, and occasionally humiliating me. The problem was it was so funny that I couldn’t resent it or risk him upping the ante, as he would do when I disappointed him, by repossessing everything that was once his from my room, leaving me in a stripped-down isolation chamber.

He had a successful career as a child actor, appearing on television in live CBC dramas and on stage; he even did commercials that ran for years, generating a small nest egg. So as soon as I was old enough, my parents allowed me to follow in his footsteps by enrolling at the Dorothy Davis and Violet Walters School of Drama, which he had attended (and so had William Shatner). It led me to much less success than him – one National Film Board production where I played a small Jewish boy, a huge stretch for me, and then an extended run at age twelve hosting a CBC television show called Tween Set, targeted at pre-adolescents.

When we moved from Montreal to Nova Scotia in 1967, he was already in university, but he came to Halifax for the summers and worked at the CBC as a summer relief announcer, filling in for vacationing regulars across radio and television. By 1972, he was busy with medical school, and I had started university. So I eagerly followed him in that summer job, spending four seasons reading radio and television news, weather and sports, voicing television commercials live to air, hosting radio interview shows and introducing late-night movies. It was the antithesis of glamour, but, like him, I cultivated the CBC sonorous-announcer voice, which made reading live the station break “This…is CBC” sound like a momentous pronouncement, especially if you had no clue what channel you were watching. And when that part of my life ended, I went to medical school.

Flash forward to the early 1990s. My brother was then Associate Pediatrician-in-Chief at the Hospital for Sick Children. His hospital decided to implement a new voice mail system and held a contest to be the voice of voice mail. He entered, auditioning over the phone by saying, “Thank you for calling the Hospital for Sick Children. If you’re calling from a touch-tone phone and your child is blue, press 2.” He won and inched further ahead in the sibling marathon, reminding me of his latest triumph at every possibility.

A few years later, the Clarke Institute implemented a similar system, leading to the retirement of the legendary queen of the switchboard, who knew everything about everyone and held strong opinions. She had occasionally allowed me to make announcements over the public address system in my best CBC voice, but it had definitely been her show.

As soon as news broke of an impending voice mail system (I admit it wasn’t headline news), I raced to the hospital administrator's office, begging to be the voice of voice mail. Understandably, he appeared baffled.

“Nobody’s asking to be the voice of voice mail,” he said.

Having a field free of competition suited me, and I was acclaimed to the post. Assuring him I was a “one-take” guy from my years in show biz, I went to my office and confidently recorded “Thank you for calling the Clarke Institute of Psychiatry” and the instructions that followed. However, I was not done. I then had to record the names of hundreds of people and key in their four-digit extensions to create a directory.

Because the Clarke attracted people from around the world, I struggled to resist my natural inclination to pronounce names as would be done in their home country. Years of dialect jokes and impersonating colleagues had prepared me for this role. Nevertheless, when I recorded the name of an Italian neuroscience researcher, I could not resist a rococo flourish, complete with rolled r’s. The next day, I encountered him in the hospital parking lot. With enthusiasm and a series of hand gestures, he said, “Professore, nobody say-a my name so good like you!” He has gone on to a distinguished international academic career while I am still updating voice mail greetings.

With the creation of CAMH in 1998, it seemed both natural and inevitable (at least to me) that I would once again record the welcoming phone message. And, once again, no one else was asking to do it, which improved my chances significantly. But CAMH got fancy. They booked a recording studio and a sound engineer, perhaps not realizing the rate-limiting step acoustically would be the tiny and tinny speaker in people’s phones. I was in and out of the studio in about three minutes, leaving fifty-seven paid-for minutes wasted. We soon reverted to recording directly into a phone what would come out of another phone.

Since 1998, I have had to re-record the message countless times — for pandemics (SARS and COVID), for changes in hospital directory and services, and for updates to our policies and procedures — “CAMH is a scent-free organization,” etc. Sometimes I meet new staff at the hospital, and they look at me with that “your voice seems familiar, but I can’t place it” gaze until the penny drops. Patients have been surprised, amused, perplexed, and possibly creeped out. But most importantly, for many years,, my late mother in Halifax could call two hospitals in downtown Toronto and hear her sons’ voices day and night. My brother left Toronto a long time ago and has since retired; someone else is the voice of voice mail at Sick Kids now. As the end of my professional career looms, I wonder who will greet people on the CAMH phone line in 2023. I recommend a contest, and not one limited to siblings.

If you know any Goldblooms, you know this story describes a perfectly normal activity. And as the expression goes, those who can record the voice mail at the office, do, and those that can’t, pick up the coffee or bring muffins. David probably does all three.

Please don’t flood the phone lines at CAMH to listen to David’s voice. Better to start a write-in campaign to have him remain the voice after he retires.

Thanks for reading, and my appreciation to David for showing us the lighter side of his job.

Alice xo

Wonderful piece - love the humour, and wish I'd cool siblings like you did! Mine were 7 and 11 years older than me and were no fun at all. Is Alice your sister?

PS it is me again, Mary Anne. I believe I did meet you years ago in the MCH ER..I was conferring with some social work students about a case and you came by to note we looked like a football huddle which of course was quite hysterical..one always needs levity in the ER!