We have been at a loss this fall. Actually we have been at many.

We’ve experienced breath-snatching news. Staggering. The kinds of tragedies the human mind denies entry, bolts every lock, tips a chair under the knob. It screams there’s no way you can fit in here.

But tragedy is a relentless intruder. And too strong. It gets in. And once inside there’s no room that can contain it, no place it might comfortably sit. It ricochets around, bouncing off walls, upsetting every neighbor below, the joints, the stomach, the heart. It opens the back door so grief can just walk right in and live here now.

Amidst all this loss, we have had to explain death to our youngest. To date, we had kept life’s worst secret, allowing him to believe in a bright, sunny world of unending good outcomes. Now, unavoidably, we must lead him out of the dark, into the dark.

Given my son’s different understanding of the world, I text his speech therapist for advice on how to talk about death and dying. She has known him for a decade. She worked with him as he was gaining words, before his brain got derailed. She worked with him as he was losing words, epilepsy feasting on all his ideas and thoughts.

She tells me to speak simply and honestly. She tells me to incorporate our beliefs, and I stop myself from asking what our beliefs are exactly because I know this is an answer key I’m supposed to have.

I sit down with my youngest and explain that his grandfather, his Boppa does not feel well. I tell him what seems to be happening. Within days, we will understand that this talk was blessedly premature—the situation seeming emergent, but then resolving and settling. My father-in-law feeling much better, the timeline altogether different than we’d feared.

But once this conversation had been started, it could not be retracted or erased with changing circumstances. His radar blazes. Radio waves bouncing off of all he had previously understood about the loveliness and safety of life hurtling back at him.

While many 14 year-olds would be stricken and quieted by this news, my son says everything he is thinking. His is an unfiltered sadness, and therefore the most purified. He is an inadvertent grief counselor, naming feelings plainly, putting them out there to be absorbed and processed.

He tells me he does not want this to happen.

I tell him I don’t either.

He asks that if this does happen, might the Sun someday return his grandfather, a hangover from a time last year when I staged a toy miracle. My son had thought the Sun had killed the toys I’d packed up and planned to purge. But his sadness over those lost toys overwhelmed me, and I returned them, letting him believe the Sun had resurrecting powers because, at the time, I thought what harm for a magical thinker. I am an idiot.

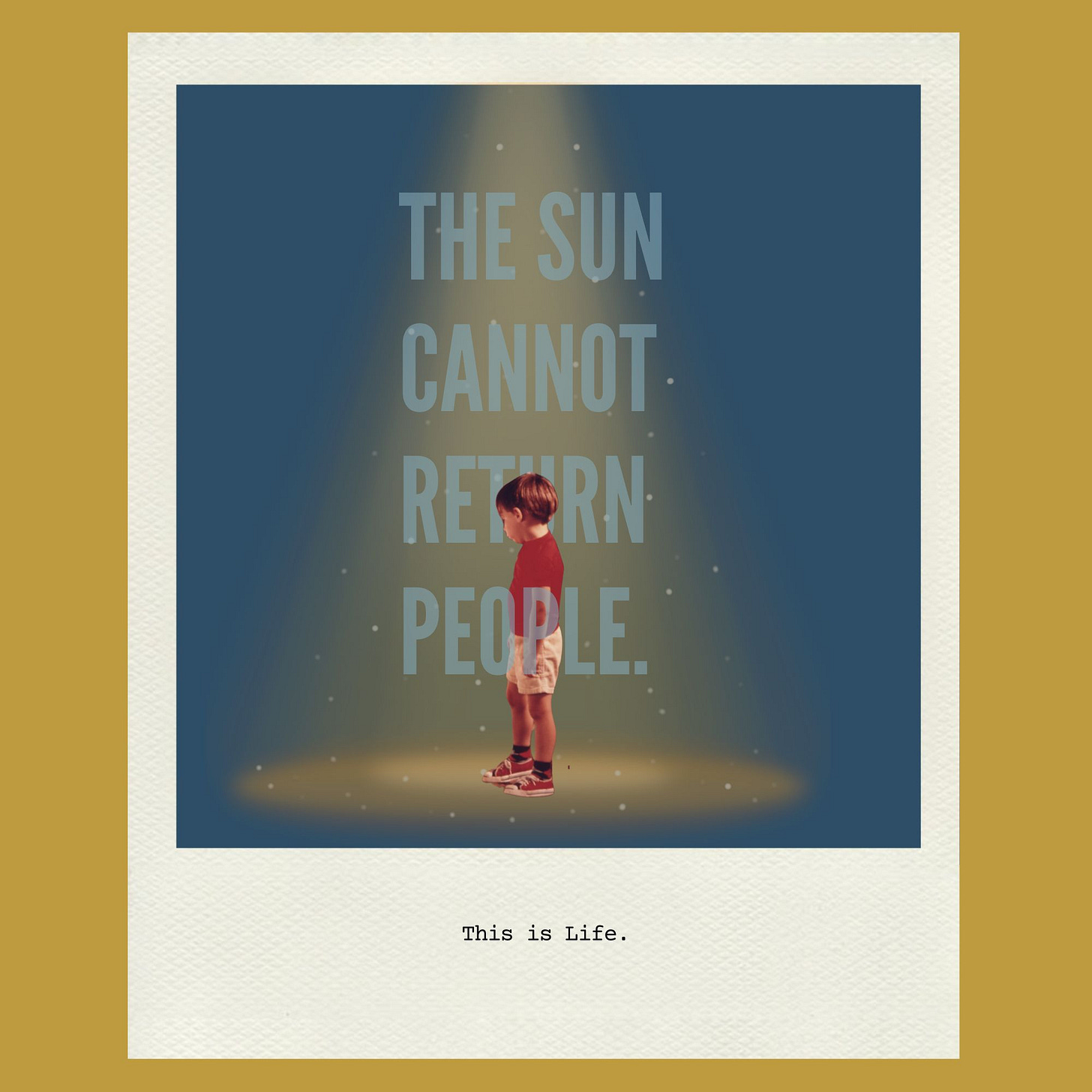

I explain that the Sun cannot return people. He doesn’t call me on it. He doesn’t ask me why I misled him. But this new information affects him physically. He slumps his shoulders, let down by the world and all its rotten details.

“But I would want him to come back.”

I fight my inner magician, the inclination to wave a wand and make this better. “I know.”

Like all the best poets, unbound by conventions, my son crystallizes emotions and often surprises. “But would there be a Spirit Boppa?” he asks a few minutes later.

When I tell him yes, he is visibly relieved. But I soon realize he’s thinking more of a clone than a spirit. He’s envisioning an exact, living replica.

I clarify. Or perhaps muddy it: we would not be able to see that kind of spirit. But we would know they were there, everywhere around us, waiting in our memories, looking down on our futures. Are these our beliefs? I’m not even sure, but the ideas seem to comfort my son.

“Daddy, would you miss Boppa?” my son asks as we walk down the back steps towards the car. We are taking my husband to the airport so he can fly to Seattle to be with his dad. Again, this urgency will end up being misplaced, but we can’t know it at the time.

“Of course, I would. He taught me everything I know.” It is always the simplest sentences that get you. Now my husband and I are both crying.

My son gangles along in front of us, thoughts probably as jumbled and stretched as his growth-spurted limbs.

“Would you say NOOOOO, DAD!” My son stretches his arms out, reaching. The unexpected theatrics make my husband and I laugh while crying, one of those heady mixed moments where you think this is life after all.

“What is that from?” I ask because I know that some of my son's best, most primary references draw from a deep, animated catalogue.

“Smurfs 2.”

As my husband gets out at the airport curb, my youngest asks if he will be back tomorrow. It’s October 30 and he knows what’s at stake: Halloween. He is to be Mario, my husband Luigi. When I tell him his dad won’t be back in time—that he needs to go be with his dad, but that we will do an extra Halloween, a night where they both dress up, sometime soon, my son’s shoulders slump again. Stupid, sad world.

“Aw man,” he turns his head to the queuing taxi line instead of his father. My son operates an uncalibrated hardship meter. This loss feels big.

We drive away, merging onto 101 South, planes blinking to our left, houses blinking to our right. Life unfolding all around us.

“Why is everyone dying these days?” my son asks. He asks this without knowing the extent of it, unaware of the rip current of loss our family cannot find the angle to swim out of.

“I don’t know.” Simple, honest.

“Is it a good question?” he asks, as he often does when he knows he’s given me pause.

“It is a very good question.”

A day later I am in Seattle. I have flown up here with my youngest.

I’m not sure I’ve ever been to Seattle in this season. We usually visit in the summer or at the holidays.

Now, outside this house, the barbecue is under cover, like a meteorologist bundled in a storm whose lone job is to just stand there and prove it is miserably rainy out today. Experience the weather, mark it.

The cocktail glasses, once busy citizens of any time after 5 pm, stay stowed in their cabinet apartment. Night falls and my father-in-law does not ask What can I getcha, Jenny? I hadn’t understood quite how I’d loved that.

At the kitchen window, camellias, blooming of all things, press their faces to the window, children at a closed storefront who know there’s something special to see inside.

There is—our time feels cozy, even beautiful. Nothing to expect of the day beyond being together. Chilly and wet outside, inside a fire and TV blazing in every room. College football games in perpetuity. My youngest, who doesn’t leave home without his Hot Wheels cars, narrates an equally perpetual race along the perimeter of the family room rug.

At night, we light candles, roast vegetables, eat and talk. And we listen. We listen to a story we’ve heard before that we’ve never heard before.

The next morning, my son walks by his grandfather’s room, spots him on the bed and yells, “Good morning, Boppa! You’re alive again today!”

This is life after all.

Wonderful narration of a parent’s journey with a child through life’s sorrows and joys.

The sun cannot return people. Oh the weight of that phrase. And the yearning your words evoke for all those in my life who will not return. Thank you (and your son) for this honest conversation and reminder that we are alive today, in this moment, and that is something to celebrate.